Oregon Art Beat

Go Your Own Way

Season 24 Episode 5 | 24m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Scott Foster, Dylan Martinez and Jill McVarish

Scott Foster is a sculptor and puppet maker who lives in Hillsboro; Dylan Martinez likes to challenge our perceptions, creating provocative and often deceptive clear glass sculptures; Astoria artist Jill McVarish creates aged-seeming paintings with scenarios that can’t quite be real, and calls her work “windows to an unknown story.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Go Your Own Way

Season 24 Episode 5 | 24m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Scott Foster is a sculptor and puppet maker who lives in Hillsboro; Dylan Martinez likes to challenge our perceptions, creating provocative and often deceptive clear glass sculptures; Astoria artist Jill McVarish creates aged-seeming paintings with scenarios that can’t quite be real, and calls her work “windows to an unknown story.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and OPB members and viewers like you.

MAN: I think I can use that.

[ ♪♪♪ ] In the commercial works, you are given an assignment.

And in my personal works, I have the freedom to do whatever I want, however I want.

WOMAN: When I was about 15 or 16, I was just, "This is it, this is what I'm doing," and I started skipping class and started painting, like, many hours every day.

MAN: It's all about the moment.

There's a beautiful artifact at the end that has no lies about what happened.

I'm just a guy in a studio trying to make some art that he's really passionate about and do it the best I can.

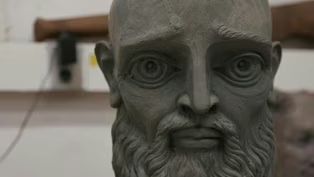

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ ♪♪♪ ] My name's Scott Foster.

I'm a sculptor.

I make things.

I'm the guy who gets in trouble at the museum for touching everything.

[ chuckles ] So it's like, "Ooh, I need to touch that."

I'm a very tactile person.

A painting or a drawing is an illusion of depth, an illusion of something in the real world, where sculpture is something in the real world.

Soon after college, I was back in Minneapolis.

I started working in commercials, doing special effects and props and stuff.

But I wanted to go to the left coast and felt like the art was a little bit more accessible here.

And there was still the old guard in Minneapolis, and it seemed like all the galleries were still pretty conservative, and that wasn't the direction I wanted to go with my art.

And so came out here to keep my pursuit of sculpting going.

♪ PJs... ♪ I started working, sculpting the characters for Will Vinton, for PJs, and then from The PJs, they had another TV show called Gary & Mike that I was the lead sculptor on.

And in between the two, there was a bunch of commercials that I sculpted the characters for.

ANNOUNCER: Fruity and Cocoa Pebbles rocks your whole mouth!

It was kind of a crash course in stop-motion animation and puppet-building.

I also worked for LAIKA on Coraline.

Got to work on Forcible and the young Forcible and Spink and Mouse and a bunch of side characters and stuff like that.

The Boxtrolls, that was really fun.

I think I did all the Red Hats' bodies and... and, yeah, just a bunch of characters for The Boxtrolls.

That was a fun project.

My personal work comes to me usually out of the need to make something.

When I get an idea for a piece, I'll do a quick sketch of it.

I'll then think about the materials I want to make it in and go from there.

And then make a mold of it and cast it.

This is a rotocasting machine.

It will tumble your mold.

So this works with gravity, pulling the resin around and around and around.

So as it's spinning around, it's coating the whole inside of the mold.

For me, it's a process.

I'm a very process-oriented person.

I like setting up my own problems and then solving them.

My first casting didn't go so well.

[ chuckles ] And then I got a face.

That was better.

And I got this out of it, some of the body, but it wasn't getting the back of the head at all.

So then I did this one, and I tried to do it with less resin, and it wasn't enough.

And so I just got this thin skin and a weird lump on the back of the head.

So the difference between doing commercial work versus your own personal work, in the commercial works, you are given an assignment and you have to work within the parameters of what is expected.

So you don't always have the freedom to do exactly what you want to do.

There she is.

I think I can use that.

You know, it's an assignment.

It's kind of like school, you know?

And then my personal works, I have the freedom to do whatever I want however I want.

In the commercial work, I usually am not too surprised when they ask for something ridiculous.

I'm usually surprised that they want it tomorrow.

[ chuckles ] I'm still like, "You can't do that overnight!"

In my own work, you never know what's around the bend, where your brain's going to go, what you're going to find.

When you start exploring in a new material or a new concept for a sculpture, the process reveals itself as you go.

The Watchers were originally conceived back in '93, I think.

I was fresh out of school and had my first studio and was sculpting away, and they just kind of came out of the blue, and I've lived with the design since.

To me, they kind of represent kind of the arrogance of humanity.

[ sander whirring ] Their long necks are like striving to look up and kind of looking down their nose at the rest of the world.

But then they're thin and emaciated and falling apart.

So they'll sit there and watch the world die without lifting a finger.

It just seems like I had to revisit that for nowadays, because I-- back when I originally made them, I thought maybe the world would change, humanity would change and change the world, but instead they just... it careened down the same path.

[ clucking softly ] Hey, chickens.

So it was early in the pandemic.

I wasn't really looking to move, and then I found this property, and then all of a sudden it got really real really fast.

And I never really realized that I had been talking about moving to the country for about 20 years.

Never thought about-- you know, I lived right on Mississippi, it was centrally located, was right-- all the shops and everything, all the fun stuff.

And so when I found this property and it was available, I kind of pounced.

It was all of a sudden like, "That is-- That's where I need to go."

[ ♪♪♪ ] Well, being a sculptor, you need a lot of space to make things.

I would never have built that Watcher back at my Mississippi studio.

I know, like, if I'm stuck on a project and getting frustrated or, like, not feeling the flow, I'll just step out and walk around the property.

It's definitely soothing.

I like having a project, I like having a creative outlet.

And when you have ten acres, you always have a project.

I think in this area, we'll probably get some-- a clearing for a sculpture.

Right now we're still just battling all the blackberries and trying to see what is here.

It's been really good to be able to just knuckle down and work.

When the sun goes down, it's dark, there's no one around.

You can just-- it's just like it's magic time.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I hope people, when they see my work, I hope it brings them joy and maybe a little sense of awe.

You know, a little bit of sense of magic.

I hope they... it moves them in some way.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Chauncey and I like to go out walking really early in the morning.

We'll go down the Riverwalk, and it's the best way I find to clear my mind, and ideas will start dropping in that way.

A lot of the things are like, "What?!

That would never happen in real life.

You'd never see two badgers kissing and exchanging flowers."

I'll take a situation that's absurd and then try to paint it so realistically that you buy it.

You look at it and you think, "Yeah, that's happening."

I found this old photograph of this girl who was all dressed up in a really fancy dress.

She was holding her dog, and she just looked really mad.

She just looked super frustrated.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Then I imagined she's doing something she shouldn't be doing in the house, and I saw her as a girl that liked to be outdoors, she didn't like to be wearing a fancy dress and she's probably, like, brought her geese into the house.

Then it's like, "How do I take the girl and her flock of geese and fit them all into the scene?"

It was always paint that called me, and I just couldn't do enough of it.

It didn't come easily to me.

I knew I had to work really hard at it, and I think when I was about 15 or 16, I was just, "This is it, this is what I'm doing," and I just started skipping class and not even going to school.

I started painting, like, many hours every day.

And ended up finishing school early just so I could get out and just get doing it all the time.

[ ♪♪♪ ] The Elmo painting started out very different than what it is right now.

I thought, "What about a polar bear in a bathtub, and I could do it in the style of this very famous David painting?"

And as I was working on it, I was falling more and more in love with the David painting and realizing that when you have a white clawfoot bathtub and a wooden box next to it and a polar bear, there's absolutely no color in it.

And then I decided, "Well, what the heck, I'll just go with the painting and throw Elmo in there because Elmo's red, he's a good actor, he's gonna be able to pull this off better."

[ ♪♪♪ ] So it became a scene, like Elmo playing the scene of the character in the David painting.

It's almost like a natural progression.

Like it's not me thinking, "Well, how would I choreograph this painting?"

It's like one thing happens, and then you realize, "Oh, it's going this way."

Yeah, it just takes on its own life.

Okay, you sit.

Can you sit?

A lot of the time when I paint kids, I really like the illustrations of children from, like, the early 1900s.

There's this sort of idealized kind of innocence about the way children are painted during that time period that I always refer to a little bit when I'm working on them because I like that look.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I'm looking for a women to be seated down with the birds.

And I've narrowed it down to these three, and I really like the hair on these two, but there's a good chance that I'll end up with someone like probably her... with probably her hair.

I really like faces.

They're the funnest and the most difficult thing for me to paint, and there's a... there's an engagement with the face.

It's psychological and it's... draws you in in a way that landscapes don't speak to me in that way.

Well, painting and any art form, it's hard because there are no right answers.

Everybody needs their own personal guidebook.

When I'm working on a painting, after the initial idea and the initial drawing, then the entire process becomes visual and I'm no longer thinking about any kind of content or meaning or anything like that.

I'm really just looking at, like, "Well, these two colors aren't working together," or, "This is in way too sharp of focus for the thing next to it," or, like, "This is creating a diagonal that's leading the eye off the page.

Is it working, is it not working?"

I know I'm done when there's nothing screaming at me from the canvas: "This isn't working!"

What I'm about to do is the last part, and it's the scariest part and sometimes kind of the funnest part, where I just take this, which is called a brayer, and just screw it up.

I'm just going to take some black paint and get it on my rolling pin here and just not look too much and just put streaks and smudges and see what happens.

Seriously, the only thing I'm thinking is, "Oh, my God, don't screw it up.

Oh, my God, don't screw it up.

Don't make myself screw it up."

That's what I'm thinking.

Now I think it's gonna be okay.

[ ♪♪♪ ] There are some days usually right about the middle of it where it's... it feels overwhelming.

And there's always this point when I'm like, "Oh, I don't know how to pull this off."

And then it's usually a day or two later, it'll turn this corner and I'll-- It's like the sun comes through, and it's just like, "Aha, there it is," you know?

My favorite part is the end, when I restretch it and I varnish it, and it's like that moment where I'm finally seeing it for the first time.

That's the point when I'm finally removed from the piece and I can actually look at it as an object instead of something that I'm grappling with.

And that is the most satisfying moment.

I feel like I've come home to Astoria.

I've lived in a lot of places and sort of tried to imitate this kind of feeling.

I've always liked old places, old buildings, dark, stormy weather.

And being here, it just feels right.

[ ♪♪♪ ] For me, being in nature is a really grounding experience.

I feel like I'm more creative when I'm out in the woods.

And I'm also, I think, inspired by, like, the overwhelming complexity that's evident everywhere around when you're wandering around in the outdoors.

The way that lightning will branch across the sky, the way a light will reflect off of a spider web, I feel like there's this poetry everywhere in the world.

It humbles me as a human and as a creator.

And I try to convey that little bit of magic in my artwork.

[ ♪♪♪ ] These sculptures start out with glass that's melted at 2,100 degrees.

I use an iron rod to dip into the molten glass and turn it and gather it out.

And then we shape the corners of the bag.

After I've pulled the corners of the bag, I use a wooden paddle to shape the glass and flatten the bottom.

One of the things I like about blowing glass so much is that it requires like 100% of your focus.

You have to shut off everything else and just be one with the material and the process.

I'll use my hot torch to spot-heat the sides of the sculpture, and I use this knife to create these indents that kind of act as wrinkles.

Dialing in the correct wrinkles is, I think, critical to selling the illusion.

Everything has to be perfect, because if one thing's out of place, your eye goes immediately to that.

Finally, the knot and tassel portion is created.

And that is kind of welded on to the top of the water bag, finishing the sculpture.

It's all about the moment.

There's a beautiful artifact at the end that has no lies about what happened.

[ ♪♪♪ ] With the water bags, I like to say it's a celebration of the material.

I think the key components that make the water bag look real are the creases of the bag and the gesture of the form.

I don't know how it works, though.

But when you do it in a certain way, it somehow just becomes this feel of water.

I actually intentionally added the air bubbles to break the illusion that it's real, because I think without the cues that it's not real, the magic wouldn't happen as fast.

People commonly ask me how do I get the water in the bag or how do I change out the water, and I have to correct them that it is in fact 100% glass.

They look more real than a real bag of water.

I can literally put a plastic bag of water next to it, and you'd rather look at the glass bag.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I mean, I thought the water bags were cool, but I had no idea that it would kind of hit a mass appeal.

I try to stay in gratitude for all the attention that it's gotten and try not to get caught up in the hype.

I'm just a guy in a studio trying to make some art that he's really passionate about and do it the best I can.

So besides the water bag sculptures I make, I've explored a variety of optical pieces.

[ ♪♪♪ ] The main part of my process is just experimenting with the material and having an open mind enough to watch for happy accidents and that I can be open to what it will reveal to me or I can reveal of it.

It's having the independence to solve the problems, to translate the ideas into a form.

[ ♪♪♪ ] One of the biggest reasons I love glass is that it's limitless.

There's no way to master it completely.

I feel like I have a pretty good foundation for understanding the material, at least how it moves.

But I also know that the possibilities are endless, which is daunting and exciting.

So I'm excited to really see what other ideas I can pull out of it.

[ birds chirping ] Yeah, I really hope that my artwork can, at a minimum, snap people out of the humdrum of typical life just for a moment of playful curiosity.

[ ♪♪♪ ] To see more stories about Oregon artists, visit our website... And for a look at the stories we're working on right now, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Really good.

[ chuckles ] Okay, you sit.

Can you sit?

Learning.

Piles of learning.

[ cat purring ] [ whispers ] You're a good cat.

Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S24 Ep5 | 7m 6s | Dylan Martinez challenges our perceptions, creating provocative clear glass sculptures. (7m 6s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S24 Ep5 | 7m 59s | Scott Foster is a sculptor and puppet maker who lives in Hillsboro. (7m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S24 Ep5 | 7m 23s | Jill McVarish paints extremely realistic scenes that could never actually happen. (7m 23s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB