Oregon Art Beat

Melissa Monroe, Jon Raymond, Helen Hồng Nguyễn

Season 27 Episode 1 | 27m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

Fiber artist Melissa Monroe, author Jon Raymond, baker Helen Hồng Nguyễn

Portland’s Melissa Monroe is redefining women’s crafts—pushing boundaries one funky creation at a time. Oregon Book Award-winning author and screenwriter Jon Raymond collaborates with filmmakers. Vietnamese American pastry chef Helen Hồng Nguyễn, known online as “The Cake Batch,” highlights her community and culture through cakes that combine Asian and Western flavors.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Melissa Monroe, Jon Raymond, Helen Hồng Nguyễn

Season 27 Episode 1 | 27m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

Portland’s Melissa Monroe is redefining women’s crafts—pushing boundaries one funky creation at a time. Oregon Book Award-winning author and screenwriter Jon Raymond collaborates with filmmakers. Vietnamese American pastry chef Helen Hồng Nguyễn, known online as “The Cake Batch,” highlights her community and culture through cakes that combine Asian and Western flavors.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

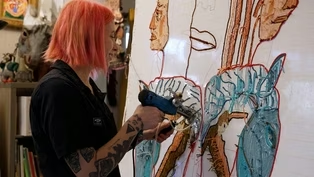

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by... [ ♪♪♪ ] [ whirring ] [ ♪♪♪ ] This is a pneumatic tufting machine.

It uses an air compressor to push yarn through the needle.

I really like how physical tufting is.

When I was just painting, I felt like I was very stagnant, like I was sitting a lot, kind of hunched over.

And when I started tufting, it was like, "Oh."

It felt really good to use my body in that way, to, like, create art.

I feel like it's really hard to stand out as a painter, and not as many people are doing the fiber crafts, so people are excited to see something new.

[ ♪♪♪ ] When I first saw Melissa's work, I was completely joyful and blown away.

MONROE: I wanted to do a teddy bear stool, and then the inside of here was hollow, and so I actually put stuffed teddy bears inside of there.

I called it "What's On the Inside Is On the Outside."

He looks surprised... with those big eyes.

MACK: Melissa brings a uniqueness.

It's so fresh!

Her view of how she's approaching imagery, animals, and color is connecting with audiences of different ages and genders-- makes it stand out.

[ hums softly ] MONROE: People love fiber.

They just want to touch it.

It has, like, this other thing that people can relate to... memory-wise, like their grandma making a quilt.

Women's crafts were not looked at as art for a long time.

There is a resurgence of women in craft.

MONROE: This is called "Happiness Piggy Bank."

MACK: Melissa's work does take women's crafts to another level... MONROE: There's this, and then you got a face there.

MACK: ...because it just brings a kind of fun, funky playfulness to it.

A lot of her tufted work is really inventive and breaking through boundaries and themes-- very freeing and celebratory.

[ ♪♪♪ ] MONROE: The masks are probably the closest to me.

I don't always sell them.

[ birds chirping ] When I put on the mask, it feels like a spiritual practice of play.

[ gulls cawing in distance ] Putting on the mask is like taking off the mask of yourself.

[ humming softly ] You don't have to have that fake smile... just be safe.

[ chuckles softly ] Ooh!

[ chuckles softly ] When I make work for myself, it just has so much more personality.

MAN: How would you describe yourself?

MONROE: I had a video on Instagram go viral, and it got 2.5 million views.

Immediately, I sold a lot of work, which was really great, and then also a lot of opportunities from galleries.

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ humming softly ] I just take pictures of stuff everywhere I go and then reference that back when I'm starting to create a piece.

So it's just like stuff from books or different artists or antique items that inspire me.

Oh, there it is.

So there's a horse that I use in the big piece.

I like that guy.

[ giggles ] Being self-taught is really great.

I don't know how to technically draw.

I almost don't want to learn how to draw too good, because I think it would just affect my style so much.

I don't have the classical training that a lot of people get, how art is supposed to look.

I'm able to create from my inner self... [ giggles softly ] ...not with those rules or teachings that might hold me back in some ways.

There.

[ ♪♪♪ ] These little scissors pop out.

I think he wants some orange lips.

[ chuckles ] That's what he's telling me right now.

I don't usually plan very much.

I let the piece grow on its own, and then I can-- It's kind of a like a surprise for myself.

[ trimmer buzzing ] [ vacuum whirring ] Really gives it more detail where I've carved, like, in between there.

[ ♪♪♪ ] A lot of times when I'm creating, blocked memories will come up or I'll be including imagery that relates to, like, my childhood.

I feel like it looks kind of embarrassed.

It's just kind of like, "Oh, I did that."

And then on this side, like, he's happy he did it, even though it was scary.

[ chuckles ] I started making art in 2012.

I was working at a coffee shop.

There was an artist painting a mural, and he was like, "Yeah, this is my job."

And I said, "People paint for a job?"

My husband at the time was a contractor, so we had, like, a lot of, like, wood and house paint and stuff like that, so I just started, like, pouring paint onto the wood and crushing glass into it.

I didn't realize, like, fully how angry I was, and it really let me let out a lot of anger.

So, like, crushing the glass, it felt like just being able to release in a healthy way.

Painting really emboldened me to, like, make decisions in my life that I needed to make.

Okay... Got divorced.

It was very scary.

I had three kids before I was 25, and I got married at 19.

I was just paying my rent by selling paintings on eBay.

It's like she's grabbing for the sky.

[ ♪♪♪ ] People are drawn to my art because of the vulnerable aspect of it.

♪ Don't lock me away ♪ ♪ Lock me away... ♪ I really like to make silly, serious artwork.

I like to, you know, maybe draw people in with, "That makes me laugh," or, "That makes me smile."

But then also have, like, this serious side of it that's like, "Oh, but there's more going on there that can connect emotionally to people."

♪ Don't lock me away ♪ ♪ I need to fly-y-y... ♪ If I can create a piece that makes you, you know, laugh and cry, I think that's the ultimate goal.

RAYMOND: There's an ancient Greek word that I've always enjoyed, "ekphrasis," which means "the joy of describing a visual image in words."

That sense of ekphrastic writing has always really thrilled me because I've always enjoyed describing things.

Like, when you feel like you've described a thing properly, that might be as close to, like, writerly pleasure as I can get.

The first novel that I worked on was called "The Half-Life," and this was in about 2000.

I was drawn, I think, to a kind of naturalist fiction and where the stakes are kind of a human scale.

I also had the idea that I wanted to write in a regionalist mode that's going to be stuff that takes place in the world that I understand, sort of in my backyard.

It was probably two years of hard writing and then another year of revisions with an editor.

I remember, like, really almost a form of, like, prayer, you know, where I was just like, "Please let this work, because I don't know what I'm going to do otherwise."

And then, amazingly, it sold.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I mean, I definitely-- I lived the dream of the '90s here.

A lot of my 20s were spent being a dilettante and doing a lot of different kinds of things-- making a movie at cable access and painting weird pictures and, like, just doing that kind of experimentation that I think is really healthy for a young, like, artistically inclined person.

I was writing art reviews for "The Oregonian."

I wrote for "Willamette Week."

I wrote for a "Snipehunt" magazine, which was an amazing quarterly punk magazine.

I really think it was radically useful as a phase of my own writing development.

To me, that's something that, like, every fiction writer should probably have to do at some point just to cure yourself of your own egomania.

So, yeah, Portland gave me, like, a ton of opportunities to write in that, like, just basically professional mode.

[ ♪♪♪ ] When I was writing "The Half-Life," my first novel, um, I wrote the essay entitled "Everywhere is Home: Some Notes on Literary Regionalism."

"The specifically regionalist novel allows for an added freedom.

The regionalist novel by its nature speaks in a voice of sidelined skepticism and long ingrown memory, the proverbial old man on the bench.

It understands that even when things happen everywhere-- the popping of a real-estate bubble, say, or the spread of some faddish spiritual belief-- they happen everywhere in particular places and to particular people in particular ways.

By molding the stuff of history into the form of local plot and character and setting, the regionalist novel allows us to see things we recognize bearing a larger meaning.

It allows us to talk back to history in some way and maybe even bend it a little, if we're lucky."

"Livability" was a collection of stories that I began before "The Half-Life."

Stories were something I could kind of finish.

You know, they were things that you could, within a human amount of time, understand if that was working or not.

I was influenced a lot on that story collection by the book "Winesburg, Ohio," an American classic that all take place in the town of Winesburg, Ohio.

It's a batch of character studies and stories that interpenetrate and kind of cross over each other but describing a small-town community, and I liked that idea as a kind of organizing principle, and I liked applying it to a medium-sized city much like Portland.

And then once I kind of understood that it was going to be that structure, then it was fun to just start kind of roving around town in my way, like, "Oh, that's a story that, like, is adjacent to that one," and, "That one kind of comes in at a different angle."

"I left on a Friday afternoon.

The minute I pulled away from the house, it started raining and it kept up on and off the whole way out.

Rain doused the windshield, followed by bolts of sun, followed by rain again, intermixed with patches of fog, sleet, and buffeting wind.

The weather might've seemed ominous if I hadn't driven the route so many times before and known there were at least eight microclimates between the city and the ocean.

For a drive to the coast in the wintertime, this was just par for the course.

I crossed the Willamette Valley, passing the fallow fruit farms and groves of oak trees and climbed into the moist coastal mountains.

The thin stands of Douglas fir, barely shielding the blasted clear-cuts, whipped by on either side, making me wonder, as always, whom the loggers thought they were fooling with their trick.

Not me."

In 2000, I met the filmmaker Todd Haynes, who moved to Portland, and I befriended him very luckily and serendipitously at that time.

I moved to New York soon thereafter, and then he came to New York to make the film "Far From Heaven."

Tell you what, let me take you to one of my favorite spots.

On good days, it's got hot food, cold drinks... And he asked me to be his assistant.

It's hard to beat that.

There you go.

Todd introduced me to his dear friend Kelly Reichardt.

She had read my first book, "The Half-Life," and liked it.

And she asked me if I had anything else that might be smaller, and I had a story called "Old Joy" that was really simple.

It was just two old friends walking in the woods and talking, and one of them going to some hot tubs.

I can't imagine another person in the world who would've seen a feature film in that story, but Kelly did.

She made it here in Oregon.

She and a very tiny crew of people came out and shot in the actual locations that the story took place in.

We discovered in that process that we really liked each other and liked talking to each other and, you know, had kind of some similar sensibilities in a way, and that led to a project that became known as "Wendy and Lucy"... Great dog, what's her name?

Uh, Lucy.

...based on another short story that I had written.

Who is that?

MAN [ over phone ]: It's your sister.

She broke down in Oregon.

What does she want us to do about it?

No address?

And no phone either?

No, not right now.

You can't get an address without an address, you can't get a job without a job.

RAYMOND: That has then led to now six movies that we've done, and, like, really, like, a blessing in my life.

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ ♪♪♪ ] [ indistinct conversation ] He mentioned that he had met you, yeah.

My latest novel is called "God and Sex," and it takes place in southern Oregon, in Ashland.

It's about a love triangle between a New Age writer, a librarian, and a botanist.

Now please welcome Jon Raymond and Justin Taylor.

[ audience applauding ] RAYMOND: "A book is round.

To a reader, it unscrolls in a single line, left to right, snaking down the page, wrapping onto the next.

But to a writer, it turns more like a wheel.

It rolls out of darkness and catches you up, trapping you inside its circle for a year, for ten years, however long it takes.

You move around inside of it, back and forth, until finally it releases you, although it never really does, not entirely.

You could say a book eats a writer many times.

You could say it eats itself.

In any case, to a writer, the idea of a beginning or an ending is absurd."

To have written that essay back in 2003 on literary regionalism, it always was very much in conversation with not only the ground, you know, the land or the people, but it also has to do with the history of the place.

"Most writers would've given up by now, but I've kept on seeking.

As a writer, I think that's what you do.

You keep peeling back, you keep whittling.

Eventually, maybe, you find the right phrasing, and then you move on to the next sentence and do it again.

The next sentence often changes something in the sentence before, and you have to go back and start all over.

Problem after problem, you try to solve it.

What is writing but the solving of impossible problems?

Or like Suzuki said, 'Nirvana is to see a thing through to the end.'"

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ ♪♪♪ ] Food, to me, is just basic necessity.

But it also means a huge deal of creativity.

It means togetherness, it means an abundance of love, an unspoken language that you can't verbally say with your mouth.

Ooh, that was legit.

I'm just saying, okay?

[ laughs ] [ ♪♪♪ ] My earliest memory of baking was actually when my father went to prison and I saw how long of hours my mom was working.

She probably put in 14 hours a day owning a nail salon.

And so I really wanted to give back to her, and the only way I knew how to was utilizing the ingredients that we had at home, so I started to make chocolate-chip cookies for her, I started to make truffles for her.

Food is so complex to me.

Because of the food insecurity that I had as a child, like going to sleep hungry at night and knowing that perhaps I would eat at school but maybe not at home, that was just really difficult for me to comprehend as a kid.

I think that that's something that every child should never experience, right?

I was getting older, I started thinking about, like, what I really wanted to do as a career, and I always loved math and I always loved art, and so I really went back and forth between being an architect or a baker or a cake decorator.

And so when looking at Food Network and seeing all of those beautiful sculptures of cakes and cookies and chocolate, I was like, "Well, that's kind of like architecture."

[ ♪♪♪ ] I started to really push myself to be more in the artist field.

I think whenever there is food involved and people, there's always a good time.

And I think that's really when I connected the two of what food can do for people and what community can do with food.

I started the Cake Batch in 2023, I believe.

I wanted to really make sure that it stood out and represented me-- something catchy, something sweet.

I actually have tattooed on me "talk sweet to me."

It was always something that I went back and forth about, because I think when you're thinking about just Asians in the culinary world, I think we have imposter syndrome.

It's like, "How is this going to be profitable but then also something that my parents are going to be proud of?"

What the Cake Batch means for me is leaving behind a legacy that not only represents Asian Americans and the flavors that I grew up knowing and loving but then opportunities for other kids to see that it is a possibility.

Whatever your background is, you can find a home in cakes.

When I think about combining Asian flavors with Western techniques, I love to compile all the different types of flavors that I had growing up-- soursop, tamarind-- wow somebody with the flavor compositions that I do have.

When they come to a pop-up and they see my ube velvet cake and they're like, "That's really unique!"

Hi.

These are gorgeous.

Thank you.

What is that?

So that is my rendition of a red velvet cake, but instead it's an ube velvet cake with a blueberry compote cream cheese whipped cream on top.

Oh, my God!

Are you serious?

Yeah.

That sounds fabulous!

Thank you.

So I really just like to play with colors and flavors at the same time and what would really complement the ube.

Something tart or sweet versus what is typical, which is just a red velvet with a cream cheese.

When we think about the American dream and what our parents want to leave behind, it's something unfathomable, outside of what they could ever imagine that is possible for them.

Giving me an opportunity to pursue something so much more, to give back to community and represent what Asian fusion pastries can look like in America.

Hello, beautiful people.

Hi.

Thank you so much for joining me today for our decorating class.

I really want to give a huge shout-out to HOLLA for inviting me today.

I know that this is really special for the mentors and mentees to come together and create something really special tonight.

Typically during these cake-decorating classes, I actually really like to tap into topics that are taboo within the Asian community.

For instance, when I speak about my family, I try not to... um, shy away from it.

I really like to talk about mental health and wellness.

HOLLA is a nonprofit that helps underprivileged youth to have different opportunities in STEM, and the theme of that class was growth and how whether your circumstances are against you in life, it doesn't predetermine where you're going to end up.

If you guys notice, I'm wearing this dress, it's called an ao dai.

It's a traditional Vietnamese dress.

I love representation.

And I'm never shy to tell people where I'm from, who my people are, where my parents come from, and their journey.

So my mom and dad actually were refugees from the Vietnam War.

When they came to America, I was the very first born.

So "Helen" obviously is not a Vietnamese name, but my Vietnamese name is "Hong."

So "Helen" means "light," and "Hong" means "rose," so my full name is "light on the rose."

And I really thank my mom for that.

There's no wrong way to do or go about life, and as long as you're not hurting anyone, as long as you are serving and trying to give back in a positive light, then to pursue it.

And I think what I'm doing is honestly extremely fulfilling.

If you want to, dream.

Dream big and do all that you can to really not only make your parents proud but yourself proud.

Yeah.

[ ♪♪♪ ] To see more stories about Oregon artists, visit our website... And for a look at the stories we're working on right now, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by...

Author and Screenwriter Jon Raymond

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep1 | 9m 36s | Novelist and screenwriter, Jonathan Raymond, is known for grounded stories of everyday life. (9m 36s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep1 | 9m 18s | An edgy tufting artist wants to make you laugh and cry. (9m 18s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep1 | 7m 9s | Vietnamese American baker, Helen Hồng Nguyễn, bakes artistic cakes reflecting her heritage. (7m 9s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB