American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs

Season 27 Episode 2 | 1h 22m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

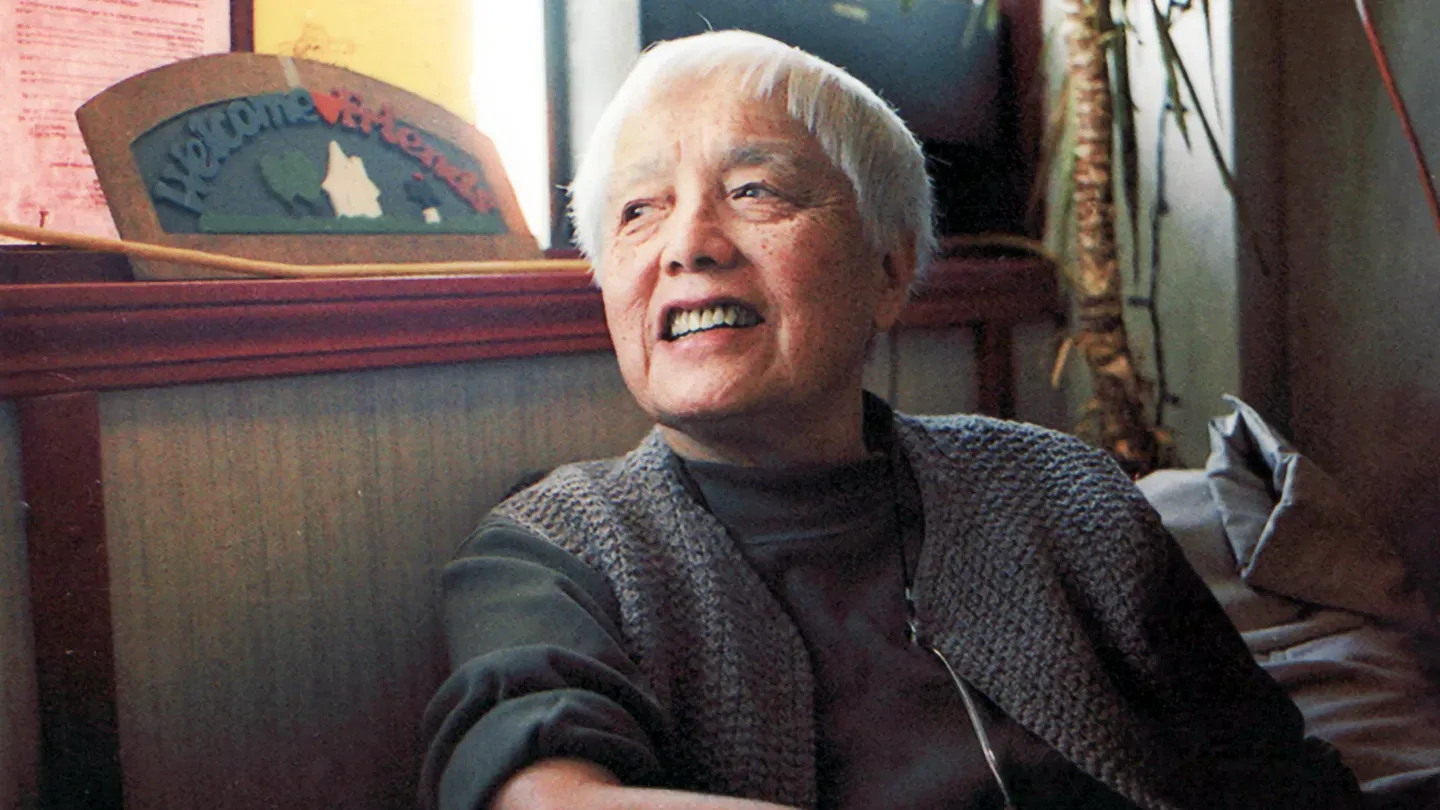

Grace Lee Boggs, 99, is a Chinese American philosopher, writer, and activist.

Grace Lee Boggs, 99, is a Chinese American philosopher, writer, and activist in Detroit with a thick FBI file and a surprising vision of what an American revolution can be. Rooted for 75 years in the labor, civil rights and Black Power movements, she challenges a new generation to throw off old assumptions, think creatively and redefine revolution for our times.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Major funding for POV is provided by PBS, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Wyncote Foundation, Reva & David Logan Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and the...

American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs

Season 27 Episode 2 | 1h 22m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

Grace Lee Boggs, 99, is a Chinese American philosopher, writer, and activist in Detroit with a thick FBI file and a surprising vision of what an American revolution can be. Rooted for 75 years in the labor, civil rights and Black Power movements, she challenges a new generation to throw off old assumptions, think creatively and redefine revolution for our times.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch POV

POV is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

POV Playlist

Every two weeks, we curate a selection of POV docs, old and new, around a central theme. Stream while you can — until the next Playlist!Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

A hypnotically cinematic love letter that untangles a family’s painful unspoken past. (1h 14m 1s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Two South African friends born intersex change what we think about being male or female. (1h 22m 54s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

A debt-laden grad turns Tokyo Uber Eats biker, confronting the gig economy's harsh truths. (52m 52s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Inuit activist Aaju Peter embarks on a personal journey for Indigenous people's rights. (1h 23m 2s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

An intimate observation of the war in Ukraine unfolds inside of a volunteer aid van. (1h 22m 9s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Revolutionary at 21. Lawmaker at 23. Most Wanted at 26. Nathan Law's fight for freedom. (1h 22m 55s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

A deaf Kurdish boy's transformative journey to communicate through learning sign language. (1h 22m 53s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Exploring the dynamic nexus of humans, animals, and science in a post-pandemic world. (1h 10m 47s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Ella Glendining embarks on a quest to connect with others who share her rare disability. (1h 22m 37s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Bordertown besties make magic of one last summer together as they face uncertain futures. (1h 15m 25s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Aspiring social worker faces the uncertainty of life as a blind, undocumented immigrant. (1h 22m 49s)

Video has Audio Description, Closed Captions

At MIT, an alum follows four African students striving to become change agents for home. (1h 22m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipBOGGS: I feel so sorry for people who are not living in Detroit.

Detroit gives a sense of epochs of civilization in a way that you don't get in a city like New York.

I mean, it's obvious by looking at it that, what was, doesn't work.

People are always striving for size -- to be a giant -- and this is a symbol of how giants fall.

Evolution is not linear.

Times interact.

History is a story, not only of the past, but of the future.

It's hard when you're young to understand how reality is constantly changing 'cause it hasn't changed so much during your lifetime.

LEE: For over a decade, I've been coming to Detroit, to this house, for an unfinished conversation.

Hello, friend.

How are you?

Come on in.

She's not my grandmother.

We're not even related.

Do you drink beer?

No, but you should have some.

I'll have a beer with you if you want to have -- You don't have to but I -- do you drink wine?

You drink beer and wine?

WOMAN: I drink everything.

You drink everything?

Okay, uh, vodka?

So, you want me to just like cut -- trim the -- Just take off some of this so it doesn't look so bad.

Okay.

You know, it's very funny what happens to the hair of old people.

You begin getting hair in your nostrils.

Oh, yeah?

Did you know that?

I'm just copying what they do in the salon.

You know, how -- it's amazing to me when I think of how, as you grow older, at least for me, just exactly what I look like doesn't matter that much to me anymore.

I've been in these same clothes for months.

It's just too much trouble to change them.

My conversations with Grace began over a decade ago when I began filming her for another documentary.

BOGGS: Lola?!

LOLA: Hello?!

BOGGS: Is Gwendolyn up there?!

WOMAN: Hi.

BOGGS: Hi.

I thought that was your car.

How are you?

I'd heard about this elderly Chinese woman who'd been a part of Detroit's African-American community for 50 years.

She seemed perfect for my earlier film, "The Grace Lee Project," which was about the many Asian-American women who share our common name.

I'm a terrible housekeeper, let me tell you that right now.

When you said, one of the reasons for your making this "Grace Lee" documentary -- I'm paraphrasing it -- was that you wanted to refute the stereotype of Asian-American women as passive, the whole thing assumed a different meaning for me.

I -- I didn't think of myself so much as Chinese.

You keep asking me this.

I didn't think of myself so much as Chinese-American.

I didn't think of myself so much as a woman.

Because the Chinese-American woman hadn't emerged, and the woman's woman hadn't emerged.

Over the years, my conversations with Grace have evolved.

BOGGS: Ah!

It's so exciting!

-Guess what?

LEE: What?

When Grace was 85, we could barely keep up with her.

This is where they've set up tables to collect the petitions.

She attended several meetings a day, taught a class, collected petitions, and constantly challenged everyone in her path.

I'm sorry.

I think that if we stick to those categories of race and class and gender, we are stuck.

As we grew closer, I began to learn more about Grace's radical past.

She's been a Marxist theoretician, a Black Power activist, and has a thick FBI file.

Grace has made more contributions to the black struggle than most black people have.

WOMAN: Thank you so much.

I was underground for almost 12 years in the United States, and Grace Lee Boggs' books were hugely influential.

It turns out that Grace has been trying to wage a revolution in the United States for the past 70 years.

But just in the time that I've known her, her ideas about revolution have started to catch fire.

What do you think of being on a t-shirt, Grace?

I never thought of myself as a t-shirt character.

WOMAN: Grace Lee Boggs, how would you describe where we stand now and how we've gotten here?

Well, I think we're in a time of great hope and great danger.

I didn't know I was searching for someone like Grace until I met her.

BOGGS: I don't know why people are so interested now.

I'm not sure why I am who I am.

I think it does have something to do with the fact that I was born female and born Chinese.

I'm not sure what that is, but I have to think that through.

And I thought that, maybe in our discussions, we would be able to explore that.

LEE: Can we go back a little bit?

How did you become a philosopher?

I'll just go back 70 years.

[Women singing] BOGGS: I went to college at Barnard at the age of 16.

College in those days was still very much an upper class culture.

I didn't want to be different.

So, I ran for office.

I was vice president of the Women's Athletic Association.

And suddenly, it all seemed barren to me.

Something seemed wrong.

MAN: Fellow workers, we want peace and prosperity in this country here!

That's what we're fighting for!

BOGGS: Union Square was full of people because of the Depression.

[Crowd booing] [Chanting] BOGGS: And even though I was not an activist growing up at all, I think that the seeds were laid, you know, in -- in my family.

Last night, I received an email from my great-niece.

And she sent me a picture that she found on the floor of her basement, of my father's restaurant on Broadway.

♫ Chin Lee's Restaurant opened in 1924.

My parents came here at immigrants.

My mother never went to school, couldn't read or write.

We lived a very comfortable existence.

And at the same time, I felt from the very beginning that there were changes that needed to take place.

So, I dropped all my classes and decided to take philosophy.

There's a class on Hegel.

And that really changed my whole way of thinking.

Hegel was a German philosopher who came of age during the French Revolution and saw its violent aftermath.

Hegel said that every idea contains its opposite, and only by struggling through those contradictions can you get closer to the truth.

That's dialectical thinking.

It means don't get stuck in old ideas.

Keep recognizing that reality is changing and that your ideas have to change.

I read Hegel's writings as if I were listening to music.

And I didn't understand it at the time, but it had stayed with me, and I have a proper respect for what reflection really entails.

MAN: You said, "The revolution is a transformation of ourselves," and I really, really agree with that.

And I wonder if your life, how did you go through that in order to become the person that you are today?

Let me tell you how I became an activist.

Uh, I was a...

I got my Ph.D. in 1940.

Just imagine that, I mean... [Laughs] And then I went out into the world and I found that even department stores would say, "We don't hire Orientals."

So, I got on a train and went to Chicago.

Found a job there in the philosophy library for $10 a week.

It wasn't very much to live on, so I found a woman who said I could stay in her basement, rent-free.

The only trouble was that I had to face a barricade of rats in order to get to the basement.

So, one day I came across a meeting of people protesting rat-infested housing.

That brought me in contact with the black community for the first time.

And I want you to think about this now -- I had never been in contact with black people before.

In 1941, the Depression had ended for white workers, but not for black workers.

I was aware that people were suffering, but it was more a statistical thing.

And here in Chicago, I was coming into contact with it as a human thing.

Being in contact with the black community brought me in contact with the 1941 March on Washington movement to demand jobs for blacks in defense plants.

Tens of thousands of blacks were ready to march on Washington.

And Roosevelt couldn't afford that to happen so he issued Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in defense plants.

I found out that if you mobilize a mass action, you can change the world.

And I thought to myself, "Boy, if a movement can achieve that, that's what I want to do with my life."

In Chicago, I realized that I'd have to do more thinking.

I went down one day to meet this West Indian Marxist C.L.R.

James -- an extraordinarily handsome black man.

And he was carrying two books -- Marx's "Capital" and Hegel's "Science of Logic."

For the next decade, Grace worked closely with C.L.R.

James, translating and embracing Marx's ideas.

This room was formerly the master bedroom.

I was a very faithful student of Marx and Engels in the 1940s.

I read very carefully almost everything that Marx wrote, and studied it and believed in it.

This is the period of Grace's life that's the hardest for someone in my generation to understand.

Here we go.

-Here I am.

LEE: Oh, there you are.

HI.

I go back and forth with her on Skype, trying to understand what she's talking about.

BOGGS: That whole question of what is dialectical humanism as contrasted with dialectical materialism, which is more in tune... BOGGS: Marx was a Hegelian who projected socialism as worker's power, whereby the workers would take over the state.

Part of Marx's theory was that if you could just get the masses angry enough, they would sweep away the existing society and emerge as a new society.

LEE: Grace joined C.L.R.

James in an off-shoot of the Socialist Workers' Party.

They took on the Party leadership, saying they had ignored racism and the potential for black workers to ignite a revolution.

Most people know me first through this pamphlet.

And my name -- I had a Party name -- Ria Stone.

LEE: What do you mean by Party name?

BOGGS: In those days, if you were in a left wing organization, you gave yourself a party name -- an underground name.

NEWSCASTER: 17 U.S. Communist leaders are arrested.

4 more Red leaders are still being sought.

The group is charged with criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of U.S. Government.

BOGGS: The generation of radicals who were left wingers had been silenced by McCarthyism.

There was always an atmosphere of fear, and we didn't begin to free ourselves from that underground mentality until the mid-'50s.

And when we decided that we were makers of the American revolution, and that we were Americans.

ANNOUNCER: In America, millions of people drive automobiles.

Most of the cars are built right here in Detroit.

The auto industry built Detroit -- made it what it is today.

BOGGS: Politics of the time said Detroit is where the workers are.

That's where you need to be.

There were two million people in the city around that time.

There was such a sense of vitality about it.

I came to Detroit to help edit the newsletter we were putting out -- Correspondence -- which would be edited, not only by workers, but by women, by young people, and by blacks.

♫Born in Alabama♫ ♫Raised in the North♫ ♫He is nothing♫ ♫But a plain black boy♫ You remember that?

BOGGS: And that's when I met Jimmy.

Jimmy Boggs volunteered to be the reporter.

And Jimmy was obviously very different, and I had never met anybody like him before.

He was militant.

He was articulate.

So, one night I invited him to dinner.

He reluctantly agreed and came late.

And I played an album -- a Louis Armstrong album that I had.

♫Doin' the Georgia Grind♫ He said he had no use for Louis Armstrong -- that Louis Armstrong was what they called an "Uncle Tom," 'cause he's always "yowsah yowsah."

So, he was -- you know, he was very unpleasant, actually.

But in the course of the evening, he asked me to marry him.

I said, "Yes."

Friends of his said I had no idea what it was like to be married to a black man.

And I didn't.

When Jimmy and I went on our honeymoon, we had to sleep in the car coming back, because we couldn't go into a motel.

LEE: Did you ever want to have children?

BOGGS: No, I never did.

I have a very wonderful philosophic view of children, but I don't know how I would do practically.

LEE: Why do you think he asked you to marry him?

You must've asked him later?

No, we never discussed it.

[Laughs] I know that sounds funny, but we never did.

Jimmy and I really never discussed personal things too much.

ANNOUNCER: "...with Ossie & Ruby!

", starring Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, with their very special guests, Grace and James Boggs.

If you'r you know, you meet somebody every now and then that you wish everybody in the world could know, like James and Grace Boggs -- those people.

OSSIE: How true.

Nobody in the whole, wide world is more dedicated to the promise and the challenge of America.

If you want to talk about diversity, Jimmy was born in the country and, you know, you'll never get the country out of him.

And there was something in me was just a rebel now.

BOGGS: Jimmy never lost his Alabama accent.

His accent was so thick that it was a little difficult to capture what he said.

If they catch you in the same God-dang car, they'd whup your butt from here to here.

♫He was born in Alabama♫ ♫He was bred in Illinois♫ ♫He was nothing but a...♫ "Plain black boy."

[Laughs] ♫Swing low♫ BOGGS: This was one of the really great migrations of this country, of black people coming up from Mississippi and Alabama to Chicago and Detroit.

♫Drive him past the pool hall♫ ♫Drive him past the show♫ BOGGS: Whole communities in the South came north, so that many of Jimmy's friends were his childhood friends.

They treated me like a member of the family.

LEE: But what did your family think?

BOGGS: My brothers lived here.

They had a lot of black friends.

It was not such a strange thing.

♫Swing low♫ BOGGS: Jimmy came to Detroit to work on the line at Chrysler.

♫Nothing but a plain black boy♫ BOGGS: He came home from work, laid down on the floor with a yellow pad and wrote.

Jimmy was a much faster writer than I.

It was just amazing the way that his pen would sort of fly, from the left-hand side to the right-hand side.

LEE: In 1963, James Boggs wrote "The American Revolution," where he foreshadowed the changes that would undermine the American working class.

BOGGS: He watched the working class expand like crazy during World War II and then steadily shrink with the introduction of what they called automation.

And he watched human beings disappearing from the line and being replaced by robots.

BOGGS: What would human beings do when they were not needed for work, for labor to produce?

I mean, that's a hell of a question to put on -- you know, on the shoulders of young people like yourself.

But, you know, you don't choose the times you live in, but you do choose who you want to be, and you do choose how you want to think.

This is where we put out our newsletter -- Correspondence.

The devastation is so fabulous, so incredible... People gone, neighborhood gone.

Jimmy would write most of the leaflets, and I would just sit and listen.

I was a Chinese-American living in an African-American community, and saw myself as a part of, and apart from the community.

This was a period that the black movement was just beginning.

1955 was the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

MARTIN LUTHER KING: We, the Negro citizens of Montgomery, Alabama, will continue to carry on our mass protest.

[Cheers] BOGGS: The Montgomery Bus Boycott was about not only transforming the system, but an example of how we ourselves change in the process of changing the system.

LEE: In the early 1960s, Grace split with the Marxist establishment to focus on a distinctly American revolution she saw emerging from the black community.

She began speaking publicly about the black revolution.

BOGGS ON TAPE: The Negro Revolt is here.

I believe that the Negro Revolt represents the beginning of an new revolutionary epoch.

I made a speech at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara.

I tried to help these male intellectuals, these liberal intellectuals, understand that the Black Movement was about something deeper than rights.

MAN: One could say for the American Negro to achieve the middle class white American standards is a revolution.

BOGGS ON TAPE: I don't think whites understand the degree to which Negroes do not want their whiteness.

I am trying to suggest that the Negro is striving to become equal to a particular image of himself that he has achieved -- that he is not trying to become equal to whites.

It was a great philosophic transition for me, which I had begun when I began examining the difference between Martin Luther King and Malcolm.

The goal of Dr. Martin Luther King is to get Negroes to forgive the people who have brutalized them for 400 years by -- by lulling them to sleep, and making them forget what those whites have done to them.

There's a great deal of difference between non-resistance to evil and non-violent resistance.

BOGGS: My relationship to King has changed over the years.

I was one of the organizers of the 1963 march down Woodward Avenue in Detroit.

MARTIN LUTHER KING: I have a dream this afternoon that one day right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house anywhere that their money will carry them.

BOGGS: But I didn't think much of him -- I really thought he was naive.

I really did, 'cause I -- I was a Malcolm person.

I would go and hear Malcolm speak.

While you're the one that makes it hard for yourself.

The white man believes you when you go to him with that old sweet-talk, 'cause you've been sweet-talking him ever since he brought you here.

BOGGS: And audiences would squirm as he would challenge them to think differently -- to transform themselves.

LEE: When we think of the Civil Rights Era, we think of the famous people.

But as Grace says, not all ideas come from the top down -- they can also percolate up from the bottom, from conversations in people's living rooms, and around their kitchen tables.

As I comb through old footage, the only evidence I found of Grace was this -- at the march she helped organize for Martin Luther King, and there's no footage of Jimmy at all.

He felt that it was much more important to keep a low profile, and to be doing the kind of thinking and organizing that was necessary.

This -- this room is essentially the same way that it's been ever since we've moved here for nearly 40 years.

Practically, everybody who's been active in the city at one time or another says that they've been in this house discussing strategy.

We see the events of 1963 through the eyes of the mass media.

Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

BOGGS: We see events like that and are not aware of the struggles that are taking place and forcing new developments.

Martin Luther King was being persecuted by the F.B.I.

during the period as being pro-communism.

Many people in the black movement were afraid that if they didn't purge themselves of left wing elements, that the movement would be destroyed.

A few months after the march she'd helped organize, Grace and others were excluded from a civil rights conference to be held in Detroit.

So, we organized our own conference and called it the Grass Roots Leadership Conference.

Jimmy was chair of the conference.

I was the secretary.

This is a picture of Jimmy talking to one of the workshops at the conference.

This is...me.

WOMAN ON TAPE: Brother Jim Boggs now has the floor.

MAN: This is part of James Boggs' F.B.I.

file.

It was very exciting to get the file.

As a historian and as a political person who's interested in their work, I hoped that this would have some new information, which it did.

LEE: Is this all of it?

WARD: This is about a third of it, actually.

LEE: A third?

Okay.

So, in the Grass Roots Leadership speech, it sounds like James is calling for violence.

You know, when I ask Grace about it, she never gives me a straight answer and I don't know why.

Straight answer about how she felt about it?

LEE: Yeah.

WARD: I think they felt that violence was already happening, and that violence was inevitable.

In fact, it was at the Grass Roots Leadership Conference where Malcolm X delivered one of his most famous speeches -- "Message to the Grassroots."

LEE: Can we play the record?

Would you like to play it?

LEE: Yeah.

MALCOLM X: We want to have just an off-the-cuff chat between you and me -- us -- concerning the difference between the black revolution and the Negro revolution.

Revolution is in Africa.

Revolution is in Asia... rearing its head in Latin America.

Only kind of revolution that's nonviolent is the Negro revolution.

WARD: Jimmy and Grace, they had been thinking about revolution for a decade and a half.

So, now they're seeing, in this particular, radical, and militant stream of black protests, a new way to think about and envision and enact an American revolution.

LEE: Inspired by the Grassroots Leadership Conference, Grace helped launch a new all-black political party.

WARD: So, when Grace helps to build the Freedom Now party, she's the only non-black person in this self-consciously all-black political organization, whose goal is, not to achieve integration, but to try to realize some power -- political power for African-Americans.

Years before it became a movement, Jimmy began writing about the importance of Black Power.

BOGGS: The word "power" strikes white people as something dangerous, threatening, and we were only talking about blacks being in office.

Back in 1963, Grace was still speaking as an outsider.

BOGGS ON TAPE: I want to make very clear that I do not claim, in any sense of the word, to be a Negro.

I have not lived all my life as a Negro, and I don't think anyone who hasn't really can speak for the Negro.

LEE: But once she becomes a Black Power activist, she starts using the word "we."

BOGGS: In the black movement, when we were demanding first class citizenship, we were saying we were being denied that.

We were very ethical, but we wanted more that that.

Right.

BOGGS: We wanted to become part of the people who took responsibility for the country.

WARD: So, by 1966, '67, she's well known, particularly in Detroit circles, but also nationally as a Black Power figure.

And I became so active in the Black Power movement that F.B.I.

records of that time say that I was probably Afro-Chinese.

[Laughter] Nobody ever really thought... [Laughs] I don't know how to say this.

But folks didn't really think about Grace as a Chinese-American.

She was Grace, you know?

She was just one of us.

As young revolutionaries would talk about certain things, and we might say, "Okay, well, you know, let's go see what Jimmy and Grace have to say about that."

WARD: Their jointly authored essay, "The City is the Black Man's Land," written in 1965, calls for black people to recognize the demographic changes taking place in American cities.

BOGGS: The freeways had been built in 1953, so by 1967, a lot of people had left.

We were a predominantly black city, which was not run by black people.

And great numbers of people who were being harassed by the police began to look upon the police as a white occupation army.

SCOTT: At 13, I had been stopped by the Detroit Police, along with my uncle, just for walking down the street.

With the emergence of Black Power, they became more aggressive and that aggressiveness was what led us to 1967.

LEE: In July of 1967, Detroit Police raided a black nightclub and sparked one of the most violent urban uprisings in American history.

[Crowd yelling] MAN: Burn, baby, burn!

[Sirens wailing] OFFICER: Back up!

Back up!

Back up!

MAN ON BULLHORN: Return to your homes and protect your own property.

The best thing you can do.

Protect your own property.

LEE: After five days, 43 people were dead.

MAN: Do he got anything on him?

Any name or anything?

It was a turning point for Detroit, and Grace has struggled to understand its significance ever since.

MAN: Let me take you back to that terrible summer of 1967, when Detroit erupted into -- into that awful riot out there.

I ask you to think about your calling it a "riot."

What would you call it?

We in Detroit call it "the rebellion."

"The rebellion"?

It was a rising up, it was a standing up.

It was the protest by a people against injustice.

So, now we ain't taking no more from nobody.

We've been -- they've been taking everything we have, and now we're showing them we ain't afraid of them no more.

We're going to get them out of jail, we don't care!

MAN: This represents a racial rebellion that goes from coast to coast.

In the city of Detroit, it represents one simple thing -- black people want control of black communities.

We can't open it!

You open it!

We can't open it!

I'll put it up and you can look in it.

MAN: I've just gone through civil guerilla warfare in Detroit.

Certainly one of the influences was those Americans who are preaching revolution in America, and I say we have to deal with such people on the basis of laws of treason.

[Applause] BOGGS: It was a turning point in my life, and it forced us to begin thinking, "What does a revolution mean?"

Grace watched how the violence of the rebellions galvanized the community, but she also saw the contradictions of where that violence would lead.

BOGGS: For a few days, there was a lot of brotherhood, but after that, we all got more scared of each other.

As a result of the rebellions, looting and crime began to seem normal and natural.

I was among the six people who were allegedly responsible for the explosion in 1967.

We actually were not in town, we were not responsible.

But we had done a lot of the agitation in relation to the propaganda.

And I did feel that, if it had not been for the active organizing and theorizing that we did, that it would not have taken the shape that it did.

In 2008, Grace invited me to a tiny island off the coast of Maine.

So, if you will be on that side of me as we go across, I'll feel more comfortable.

She and Jimmy began coming here every year after the turbulent summer of 1967.

BOGGS: Getting more rickety by the day.

I hoped that coming here would help me understand how she went from being the '60s militant to the woman I know today.

BOGGS: As we sat here, against the background of the ocean, of the trees, we just began talking.

And we started these conversations, which are now published as "Conversations in Maine."

Every summer, Grace and Jimmy would join their old friends, Lyman and Freddy Paine, in Lyman's family home.

They had known each other since the 1940s when they worked with C.L.R.

James.

BOGGS: Over the years, we had these long conversations.

What are the depths of it?

BOGGS: And what changes have to take place in people in order to bring about a revolution?

Talking together, we were able to create a kind of consciousness among ourselves.

And I think we realized a rebellion is an outburst of anger.

But it's not revolution.

Revolution is evolution towards something much grander in terms of what it means to be a human being.

WOMAN: You can have discussion, you can have a meal, you can plot, whatever.

We plotted picket lines, we plotted anything we wished to do.

At the end, it was always, "Okay, let's put on some music, and let's relax."

And music, relaxing and dancing, part of the thing.

Hey!

So then, tradition has it.

Welcome to the house.

WOMAN: Looks pretty, doesn't it?

But listen... WOMAN: Well, I started going in '78, and then went back every year with Grace and Jim.

It was my first exposure to talking about what's this all mean, where are we headed?

BOGGS: Ideas matter.

And when you take a position, you should try and examine what its implications are.

That it is not enough to say, "This is what I think, this is what I feel," and leave it at that.

I can remember, for example... You mind if I just change my tape for a moment?

Uh... Grace has stacks physical proof of how much she values conversation.

WOMAN: The only models that whites have... BOGGS: We're the only living things that have conversations, as far as we know.

When you have a conversation, you never know what's going to come out of your mouth, or out of somebody else's mouth.

Go ahead, Grace.

Come on.

Freddy, I'm sorry, I don't think this is [bleep].

I really don't.

Okay, I'm sorry.

It all goes back to Hegel.

For Grace, conversation is where you try to honestly confront the limits of your own ideas in order to come to a new understanding.

WOMAN: Talk is cheap.

But they talk about their feelings, about what was important about their feelings and -- Look, you know, Nancy, I really, really, really get ex-- I'm sorry.

When you just say, "Talk is cheap," like that, I -- I can't -- I can't -- I find it very, very difficult to take, I want to tell you honestly.

Their talk was not cheap!

NANCY: You're making an in-- You're saying that -- You're saying things like, "Talk is cheap."

NANCY: No, you're not listening to me.

You're saying that we can talk about what's important in a revolutionary movement, but we don't have to act like it.

Grace was hard on people, there's no question about it.

Grace, I think what Nancy's raising is -- You know, I sometimes think she didn't mean it personally.

But she would be so intent on whatever her idea was, and be so sure that she needed to push you in that, and if you resisted, she'd get mad.

I think it's hypocritical.

BOGGS: Well, I -- I'm sorry.

This, you know, I feel the number of adjectives that you are using with regard to it are very excessive.

I really do.

And I think you really should look at it.

NANCY: Well, I should.

LEE: Did she make people cry?

Oh, God, yeah, she made all kinds of people cry.

[Laughs] Myself included.

But all kinds of people, yeah.

I could probably give you a rather long list.

Two...three... Freddy, in the afternoon, would make cranberry sauce, and I would read to her.

"Jackson understood that the psychic scars carried by white workers were as damaging to our national well being as the scars carried by African-Americans."

There are times when expanding our imaginations is what is required.

The radical movement has overemphasized the role of activism and underestimated the role of reflection.

MAN: "Black Workers' Power!"

ALL: Black Workers' Power!

WOMAN:♫I watch you go to church on Sunday♫ MAN:♫Then you forget all you learned ♫On Monday♫ SCOTT: After 1967, they had the major white flight out of the city of Detroit.

♫Run, Charlie♫ Some neighborhoods literally turned from white to black overnight.

♫ ♫Run, Charlie, Run♫ BOGGS: After the rebellion, there was a great sense of power, and that sense that the city belonged to us.

HOWELL: What a lot of people don't realize is that the call of Black Power was to the country -- it wasn't just to African-Americans.

And Detroit was exciting, because it was emerging Black Power.

MAN: I came to Detroit in 1970.

I got a job in the Ford plant.

I was there to be part of a revolution.

I started coming by Jimmy and Grace's house to be part of the study groups.

HOWELL: It started off with discussions around current events.

If, after about four to six months, people thought you were a serious person, you then got invited to what was called a "revolutionary study group."

And that was based around revolution and evolution in the 20th century.

During Grace's lifetime, hundreds of revolutions have taken place around the world.

BOGGS: People thought of revolution chiefly in terms of taking state power.

But we've had revolutions and we've seen how the states which they have created have turned out to be like replicas of the states which they opposed.

You have to bring those two words together and recognize that we are responsible for the evolution of the human species.

It's a question of two-sided transformation, and not just the oppressed person -- it's the oppressor.

We had to change ourselves in order to change the world.

LEE: How does that relate specifically to you?

Well, one of the things I think you have to understand is I grew up in a male-oriented movement.

I subordinated myself very consciously.

Then what I was noticing was that there were a lot of women around, and I felt that if I didn't begin struggling with Jimmy, I would give them the completely wrong impression.

HOWELL: She and Jimmy would fight like mad over stuff, but I also think it was a strategy she was learning and trying out.

And even in the interplay between them, you saw a microcosm of the struggle that people were having otherwise.

HOWELL: Here in Detroit, people literally thought the revolution was next week -- that we would be creating something very, very new, and, in fact, we did.

SCOTT: In the early 1970s, there were a number of people who had formerly been in the old left movements who were emerging and running for office.

Coleman Alexander Young had helped organize Ford in the 1940s.

In the 1950s, he had been a victim of the McCarthy Era.

He was about to go to prison.

You know, they were going to send him to prison as a communist.

In 1973, Coleman Young ran for mayor against the former police commissioner and won.

BOGGS: The readiness of people to accept a black mayor, I think was tied very much to the recognition that a white mayor would no longer be able to maintain law and order.

To all dope pushers, to all rip-off artists, I don't give a damn if they're black or white, if they wear a super-fly suit or a blue uniform and silver badges -- hit the road!

[Applause] HOWELL: I remember that sense of incredible hope.

FELDMAN: You were standing up against racism, you were standing up for change, and it does bring change.

♫Hello, Detroit♫ ♫You've won♫ ♫My heart♫ ♫Your renaissance and waterfronts♫ ♫Gives you a flair of...♫ We are 25 million strong!

Cut us in, or cut it out!

It is a new ball game!

[Cheers] Don't stop at the mayor's office -- go on higher.

Our time has come!

A new day has begun!

BOGS: My eyes have been glued to the screen.

The sheer size of that crowd... Oh!

LEE: Do you wish you were there?

No.

First of all, I'd be thinking about different things.

When you get old, I'd be thinking of where the toilets are... [Laughs] NEWSCASTER: From Pacifica, this is "Democracy Now!"

Grace Lee Boggs, did you watch the inauguration in Detroit?

I sure did.

I certainly did.

One of the difficulties when you're coming out of oppression, and out of a bitter past, is that you get a concept of a messiah, and you expect too much from your leaders.

And I think we have to get to that point that we are the leaders we've been looking for.

For us, they fought and died.

BOGGS: One learns very soon that the changes we need are not going to come from the top by electing somebody else.

...and worked 'til their hands were raw, so that we might live a better life.

And I recognize that crime is a problem.

I lay it side by side with unemployment... SCOTT: Well, I'm going to tell you what it felt like when Coleman Young won.

Somebody comes in and he says, "Free at last, free at last, white folks can kiss our ass."

I started to cry.

I cried because I said, "These folks really think this means freedom."

And that's when I knew that we were in for a rough ride.

NEWSCASTER: The unsold inventory has been unusually large this year because of continuing declines in new car sales.

FELDMAN: Toyota, Datsun, Honda -- they all started selling vehicles in the United States.

LEE: As auto companies began moving factories overseas, unemployment in Detroit steadily rose.

People fled the city as the crime rate exploded.

BOGGS: I began to see that Black Power could not solve the crisis that was developing.

LEE: Desperate to keep jobs in Detroit, Coleman Young turned to the corporate leaders he once fought against.

May I say to you, Mayor Young, speaking for the business leadership of the Detroit Metropolitan area, that you have our support.

FELDMAN: It really became business as usual.

Coleman Young was running the city, but his only vision for economics was what he was raised with -- that large General Motors plant, large production facilities would be the way that you could create economic security.

The Ford Rouge plant in the 1930s had 95,000 people working under one roof.

Today, there are fewer than 100,000 GM, Ford, and Chrysler workers in the United Auto Workers in the United States -- total.

BOGGS: That's how history changes you... how hard it is to become part of the new and not get stuck in the old, and how powerful that tendency is to keep you boxed into the past.

NEWSCASTER: Detroit has, by far, the highest murder rate in the nation...

Number of families requiring food assistance increased fivefold from 1981...

The city that is second in the nation with drug-related crime.

MAN: ♫We love our neighborhood♫ ALL:♫Get off the crack and don't come back♫ ♫We love our neighborhood♫ ♫Get off the crack and don't come back♫ SCOTT: The drug wars was devastating.

Everything else was dealing with the aftermath of that.

How do you deal with people breaking into your home?

How do you deal with murder on your street?

♫Run and hide♫ SCOTT: Do you do a demonstration in front of a dope house?

You can do that.

But we were getting to a point where we needed a picket sign inside of our heads and hearts.

WOMAN: You know, sometimes when we're on the ground, working in the field, people are up against some really hard conditions.

How do you... How do you prevent yourself from burnout?

And...[crying] how do you... continue to feel like you could... work with folks and continue to motivate them?

I stayed involved because I stayed in one place for the last 55 years.

♫Run and hide♫ ♫Run and hide♫ I think it's 'cause I grew to love Detroit and to feel responsible for Detroit that I was able to grow.

And find one thing after another, and trying to learn from everything that I tried.

That's the only way.

I mean, the illusion there's a quick answer leads to burnout.

♫Hey hey, ho ho♫ LEE: As Grace struggled to understand the violence that was devastating her community, she returned to the evolving ideas of Malcolm and Martin.

BOGGS: Malcolm really struggled and toward the end of his life began to be critical of black nationalism, and went down to make common cause with King.

After Malcolm was killed, I would attend these meetings, and I would see young people, 14, 15, 16 year olds, getting up and limiting Malcolm to sort of "meet violence with violence."

And I knew something was terribly wrong.

Why is nonviolence such an important -- not just a tactic, not just a strategy, but an important philosophy?

Because it respects the capacity of human beings to grow.

It gives them the opportunity to grow their souls, and we owe that to each other.

And I -- it has taken me a long time to learn that.

[Applause] All you who are clapping, I suggest you do some more thinking.

[Laughter] MAN: Our father, we come now, we pray that you to look over these our people this evening.

BOGGS: But as I saw the violence increase in our cities, I wondered would it have been possible to combine Malcolm's militancy with King's nonviolence?

I began reading King much more carefully.

In 1965, the explosion in Watts burst out.

And King flew to California, and he was amazed to hear that these young people had never heard of him -- that they thought nonviolence was foolish.

And he began thinking, "What do I do about that?"

MARTIN LUTHER KING: I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values.

We must rapidly begin... [Applause] We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.

[Applause] BOGGS: King said, what our young people in our dying cities need are direct-action programs, which enable them to transform themselves and their institutions at the same time.

DJ: Right now, bright sunshine.

It's 66 degrees downtown... BOGGS: It's an incredible city.

That's one of the things that's very exciting about Detroit also, because it's not going to be reindustrialized.

Something else has got to come out of it.

And we really think about, how do we rebuild it now?

How do we take the space?

How do we make something new out of it?

LEE: In 1992, Jimmy and Grace helped launch a program called "Detroit Summer," to transform the vacant lots and buildings of Detroit, hoping that in the process, young people would transform themselves.

Thank you for coming back, Carol.

When they can see themselves making a difference, they also become different.

That has to be part -- an integral part of the process of revolution.

I have one line.

Grace gave it to me Friday morning.

And part of our organizing work, we want to bring the neighbor back to the hood.

How you doing?

WOMAN: I was 16, and I volunteered to be a part of Detroit Summer.

I was actually the very first person to sign up.

And I had profound questions.

Why does everybody talk about Detroit in the past tense, you know, as just a sty?

I'm living in Detroit now, and I don't want to feel inferior all the time because Detroit isn't the city that it used to be.

Young people.

When I first met Grace, Detroit Summer had been around for eight years.

Grace gave us a tour of the community gardens and the murals, which seem nice, but I wasn't sure what the point was.

What does this -- what does this mean?

BOGGS: You'll have to get them, ask them.

Oh, okay.

All right.

It would take another decade for me to really get it.

WOMAN: We started Back Alley Bikes as a way to get kids to their project sites.

And now we just have so many coming in that we just can't handle them, really.

[Both laughing] BOGGS: That's amazing.

This idea of Back Alley Bikes was a very small thing -- seed Gayle planted just a few years ago -- and now it's mushroomed to all these bikes, and the idea of a bike auction.

I mean, that's the idea.

It's sort of one thing leading organically to another.

It takes time but, you know, it's -- it's a question, when you think about time in another way.

JIMMY: Let me tell you something.

Grace and I being ourselves is nobody.

It is only in relationship to other bodies and many somebodies that anybody's somebody.

Let me tell you that.

Don't get it in your cotton-picking mind that you are somebody yourself.

BOGGS: The day after Jimmy died, I got up in the morning and I decided to have some oatmeal for breakfast, and that I would do that from now on.

That I would not -- I would just establish a routine.

One gets used to living alone.

I wish Jimmy were here.

He would love to be here.

But he isn't.

So, life continues to be very challenging.

It's a long time, you know, and a lot has happened since.

I don't think that enough has been written by women who are on their own after 40 years of close relationship to people.

[Jimmy on video] You look at the pictures of me on that DVD... And not only I know, but ain't nobody... BOGGS: I was so demure, I was so -- so overshadowed.

I remember someone saying they wanted to write a biography of Jimmy, and my writing to a publisher and asking if they would be interested.

And they said they would be more interested in a biography -- an autobiography -- by me.

And I couldn't believe it.

Why would they be interested in me?

And it wasn't until I did that that I knew who I was to some degree, and could begin to develop myself.

LEE: Grace's autobiography introduced her to a new generation of people beyond Detroit, especially Asian-Americans, like me.

BOGGS: People began asking me to speak on the Asian-American movement, and I discovered my ignorance.

People are so searching for icons that they sort of fixed on me, even though I wasn't an Asian-American icon.

The varieties of Asian-Americans that I see around here is so enormous.

I mean, it's just incredible.

MAN: I met Grace when I was still struggling with a sense of, you know, where do Asians fit in a world that's mostly white and black?

When we think about Grace in the 20th century, she is very much an outsider.

In the 21st century, she represents the uniting of people from different races and different backgrounds in a way that is now defining America.

Let me make a challenge to you, okay?

With people of color becoming the new American majority in many parts of the country, how are we going to create a new vision for this country -- a vision of a new kind of human being, which is what is demanded at this moment?

So, that's your challenge.

And, so, the Black Power movement became... LEE: Even in her 90s, Grace still travels the country talking about revolution, but she always brings the conversation back to Detroit.

I can't begin to tell you the number of young people who come to Detroit, and they come in order to be part of this new world that is being created.

KURASHIGE: How many of you have been to Detroit before?

You're going to see a lot of abandonment, but you'll see it's about rebuilding a new way of life for people who've been completely left behind by a capitalist system, which has gone elsewhere looking for profit.

People had to find new ways to promote economic survival when unemployment was reaching upwards of 50% as it has now.

Grace was at the forefront of the movement in Detroit that were developing urban gardens, and eventually even bigger urban farms.

WOMAN: Most gardeners, I'd say, 90% of gardeners don't garden on land they own.

They're gardening on vacant lots that are next to their house, or across the street.

BOGGS: I think of gardens as the basis of hope, or something that was unthinkable just a few years ago.

FELDMAN: As Detroit Summer was emerging, and they were doing murals and they were doing gardens, the question I was always asking was, "What does this have to do with the movement?

They're nice projects."

I think what I've begun to understand is that individuals who experience and get involved in those projects become leaders, become thinkers, become compassionate people that see themselves as makers of history.

20 years after first volunteering for Detroit Summer, Julia Putnam is planning a school on Detroit's east side -- the Boggs Educational Center.

PUTNAM: So, this is the house we saw when we envisioned this place as a school, and got really excited about the idea of school as another home.

And it's really gutted, to the point where... the possibilities are endless.

BOGGS: It starts with imagining the kids in the space, and in the community, And how it's going to grow more by trial and error than it's going to grow by blueprint.

PUTNAM: That's always my downfall.

[Laughs] I think I can get it perfect and then do it, as opposed to knowing that you do it by making mistakes.

BOGGS: You make your path by walking it.

Mmm!

[Laughs] ♫Detroit in the summer♫ ♫It's more than a season♫ ♫When I moved to the city♫ ♫Was the core of the reason♫ ♫Can I clarify♫ ♫All the distortion you seeing♫ ♫Gotta break your mind out of prison♫ ♫While the warden is sleeping♫ One of my favorite quotes by Grace is that, "Creativity is the key to human liberation."

I actually try to spend my birthday every year with Grace, having like a one-on-one conversation.

Hey, Grace?

BOGGS: Hi.

How are you?

WEAVER: What's up?

She's still seeking new answers.

She's still asking me about hip-hop, so to me, the way that she has conversation is such an artistic approach.

Conversation is now Grace's main form of activism.

She's constantly inviting people into her home.

But it's not just a chat.

She pushes everyone to evolve their ideas.

MAN: You begin to shape the idea of what you mean by quality education.

You know, and so -- BOGGS: First of all, everybody who talks about quality education is really talking about, "How can our people become more like white people and advance in the system?"

I don't -- you know, I beg to differ with you on that.

BOGGS: Most people think of ideas as fixed.

Ideas have their power because they're not fixed.

And once they become fixed, they're already dead.

Making a paragon shift in the educational system.

GLOVER: Well, what subject is that technological shift at most evident?

Mathematics.

No, it's not mathematics.

No, it's not mathematics.

-I believe it is.

-No, I don't.

That's basically what we're trying to tell our kids to do.

"You've got to learn mathematics.

You've got to learn technology so that we can compete on the world market."

GLOVER: That becomes part of it, but it doesn't have to be solely that.

No, but there's a whole lot of that.

GLOVER: Well, it's a whole lot of that.

That's what kids are rejecting.

And I don't blame them.

So, we've got to think about what is education for?

You have me thinking.

[Both laughing] BOGGS: People talk about the light bulb going on, I think a light bulb goes on very often in conversations that people have, and we don't pay attention to it, 'cause it's so much a part of life.

These are five books that I teach of education.

It's talking about... And after every conversation, Grace gives you something to read.

Six.

Six books?

I'm going to -- okay.

As you interviewed me this morning, I thought, how much our ideas come out of conversation, and we don't recognize that -- that our stories are basically on the dialogues that we carry on with one another, as we sort of begin looking at the past and the future together.

Over the years, my relationship with Grace has evolved.

"Amazing Grace."

[Laughs] Is that what it says?

I've seen put her on a pedestal, and I realize I've been doing the same thing.

But these days, I find myself pushing back.

Come here and give me a hand.

LEE: Okay.

Grace is so good at subtly directing conversations.

She deflects the personal questions and puts a positive spin on everything.

It's starting to drive me crazy.

Were there ever times where you felt regret about anything?

I don't think I've ever felt regret about what's happened to me over my life, or anything that I did or didn't do.

LEE: Okay.

I've always thought of the negative as an opportunity to create a positive.

LEE: Always?

You use the word "frustration," and I think you... that sort of provides a sort of framework for the questions you've been asking.

And frustration is not one of the things that I've felt through my life.

I would never describe my life as having been frustrated at any point.

I guess I'm trying to find like some kind of connection to you.

You're so confident about your positions and your ideas.

Well, you know, if I had undertaken the challenges that other people have undertaken, if I had decided to become a mother, for example, which you have decided to be, I could imagine a lot of frustrations.

So, in that sense, I've lived more the life of a man than of a woman.

I can't relate to someone who doesn't doubt themselves, is what I'm saying.

[Laughs] Or question, you know, "Did I ever make a mistake?"

'Cause your whole thing about self-transformation should require like an internal struggle.

Well, I think, probably... That's -- that's a criticism, that I should be making of myself that -- That I should talk so much about transformation, and not experiencing it.

I think this encounter will be with me for quite a while.

I'll have to sort of internalize it, and see what it means to me.

You know, it has to be incorporated into who I am, and my trajectory.

And that will probably happen because I'm pretty good at that.

[Laughs] Every time I visit Detroit, I wonder if this will be my last conversation with Grace.

[Grunts] Oh, dear.

It takes so much effort just to get around.

On the one hand, I have endured, and on the other hand, I have changed.

I can remember swearing when I was young that I would not change, 'cause if I changed, I would betray the revolution.

And as I was growing older, I've understood that I should change.

And changing was really more honorable than not changing.

NEWSCASTER: It's the 97th birthday of writer and radical activist Grace Lee Boggs.

WOMAN: Good morning, Miss Grace.

1...2... 3... 4... Time is irreversible.

The arrow is pointing forward.

We have no idea what the future holds.

What's very hard for older people to understand -- You know, it's like, someone said, you can't practice being president -- you can't practice being old, and aging is not for sissies.

You don't know how much... How much pride, how much responsibility, how much fear are tied up in that.

I thought about what it was like to live longer than anybody else, longer than your siblings.

You'd be amazed how alone you feel in the world.

I am very conscious that I'm in the process of dying.

To me, that's not a terrible thing.

So, I see this as a period of transition, that I can make a transition by the things that I choose to engage in.

WOMAN: Hey, Grace.

We're making that bacon that you had left over.

BOGGS: Hi, everybody.

I'm very conscious, in that sense, of time.

How long will I live?

How long should I live?

At the same time, I'm very conscious of what time it is on the clock of the world.

[Clock ticking] As I have grown older, I think more in terms of centuries, whereas eight or nine years ago, I was only talking about decades.

And it's so obvious that we are coming to a huge turning point.

You begin with a protest, but you have to move on from there.

But just being angry, just being resentful, just being outraged does not constitute revolution.

So many institutions of our society need reinventing.

The time has come for a new dream.

That's what being a revolutionary is.

I don't know what the next American revolution is going to be like.

But you might be able to imagine it if your imagination were rich enough.

♫So let's love Nature right now with all our hearts♫ ♫That's right, this present moment♫ ♫Is a great place to start♫ ♫And when we are smiling and singing our song♫ ♫Other people hear us and may want to sing along♫ ♫They sing♫ ♫I love Nature♫ ♫Nature is cool♫ ♫The forest is my classroom...♫ BOGGS: Revolutionaries -- that's what you are.

That's what we want all children to become.

♫On this school all life depends♫ PBS.

Your home for independent film.

American Revolutionary: Black Power

Grace Lee Boggs on joining the Black Power movement in Detroit. (5m 50s)

American Revolutionary: Conversations in Maine

Grace Lee Boggs discusses Conversations in Maine. (2m 14s)

American Revolutionary: Filmmaker Interview

Grace Lee on the making of American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs. (21m 36s)

American Revolutionary: Meet Grace Lee Boggs

Meet Grace Lee Boggs, waging a revolution for over 75 years. (6m 49s)

American Revolutionary: On Revolution at Berkeley

On Revolution: A conversation between Grace Lee Boggs and Angela Davis at UC Berkeley. (12m 30s)

American Revolutionary - Trailer

Meet Grace Lee Boggs, waging a revolution for 75 years in Detroit (2m 13s)

American Revolutionary: Violence vs. Non-Violence

Grace Lee Boggs talks about white flight and the impact on Detroit race relations. (4m 17s)

American Revolutionary: Violence vs. Non-Violence 2

Grace Lee Boggs explains how she struggled to understand the violence in her community. (1m 22s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major funding for POV is provided by PBS, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Wyncote Foundation, Reva & David Logan Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and the...