Oregon Art Beat

Reclamation

Season 24 Episode 2 | 25m 54sVideo has Closed Captions

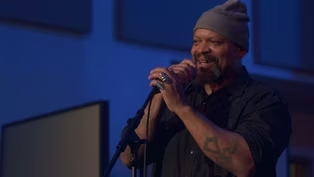

Hip Hop Artist Mic Crenshaw; Champion powwow dancer and yoga teacher, Acosia Red Elk.

Respected hip hop artist, Portland Poetry Slam champion and educator Mic Crenshaw uses his creativity to encourage emerging artists and support local and global activism; From her home on the Umatilla Reservation, Acosia Red Elk travels the world as a champion powwow dancer, yoga teacher and collaborator with artists such as Portugal. The Man.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Reclamation

Season 24 Episode 2 | 25m 54sVideo has Closed Captions

Respected hip hop artist, Portland Poetry Slam champion and educator Mic Crenshaw uses his creativity to encourage emerging artists and support local and global activism; From her home on the Umatilla Reservation, Acosia Red Elk travels the world as a champion powwow dancer, yoga teacher and collaborator with artists such as Portugal. The Man.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and OPB members and viewers like you.

♪ They all admit it I'm authentic ♪ ♪ Strong, gifted And positive... ♪ How do I become who I really am so that the authenticity of what I'm saying can be felt by my audience?

The best way for me as a human being to try to impact things in a positive way is to be creative and to use art.

♪ Internal, external Eternal creation ♪ WOMAN: The sound that the regalia makes, it ripples outward and people feel it.

See how it has that sound?

[ drums beating ] I had to learn how to start trusting my voice as a leader and gaining that confidence, knowing that I was carrying the name of my tribe with me.

[ ♪♪♪ ] ♪ I'm leaving today ♪ ♪ Big jet plane Fly far away ♪ ♪ Vampires gotta die Empires gotta fall ♪ ♪ There won't be no compromise I want freedom for us all ♪ ♪ Sure as my cheekbones Are prominent ♪ ♪ You know I'mma be Mobbin' on the continent ♪ ♪ White supremacy's Dominant here ♪ ♪ My conglomerate's clear ♪ ♪ It will disappear Even in this hemisphere... ♪ This is in a historically Black community, right?

And it's important for this to be happening over here, because there's a reclamation going on where people are intentionally trying to create culturally activity that's a reflection of not only the historic Black community but current Black cultural expression in the city.

♪ If I don't have an exit plan Established then forget it ♪ ♪ Tanzania is the bomb ♪ ♪ I might be there Before too long ♪ ♪ I admire the environment... ♪ My name is Mic Crenshaw.

I'm a cultural activist, so I'm combining my work as a hip-hop artist, an educator, and a social justice activist.

My creative process is lyric-driven.

Lyrics will come to me.

It often starts with a line, you know?

There'll be one line that will come to me, and I'll be like, okay, how should that line flow into the next line?

♪ I thought about my whole world Decided I'm not... ♪ Some of these concepts, the lines are things that I've thought about, you know, forever.

♪ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr... ♪ I started to toy with the idea of being a professional artist, but it wasn't until I was in my 20s that I started to take my desire to be a lyricist seriously.

♪ I'm in the fast lane Smashing, passing RVs ♪ ♪ 95 degrees Against the breeze ♪ ♪ Unpredictable smoothness My vehicle movement ♪ ♪ It's spectacular Intergalactic cruise ship ♪ ♪ The night at my back There is no confusion ♪ ♪ The wind and the road And the engine's music ♪ ♪ All it really is Is somethin' to do... ♪ ♪ The rewards of knowing That everything is perfect ♪ ♪ Divine time in alignment Refinement of purpose ♪ ♪ The service of my Central nervous system ♪ In the '90s in the U.S., all the most popular rap was talking about getting money and selling dope and being rich, and I was like, that's not really who I am.

Okay, play it again.

So how do I become who I really am so that the authenticity of what I'm saying can be felt by my audience?

That was when the political consciousness that had long been part of my development started to inform my lyricism.

And I guess I became a political rapper.

♪ I'm in solidarity ♪ ♪ With those who seek Their sovereignty ♪ ♪ Turn around Heard a sound ♪ ♪ Whole lot of folks Yelling, "Burn it down!"

♪ ♪ A lot of us want To make it out ♪ ♪ I'm like, what can I do Right now?

♪ You too, man.

Thank you.

We'll talk soon.

-Yeah, see you soon.

-Cool.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I was born in Chicago on the South Side, 1970.

You know, Black urban life was what I was used to.

I went to junior high in St. Paul and finished high school in Minneapolis and went to a little college.

The soft psychological violence of racism and feeling socially ostracized and the physical violence of being bullied and then having to stick up for myself time and time again, I think that's what shaped my desire to be more of a rebel.

And, you know, by the time I really felt like I fit in, it was only in the punk scene.

[ ♪♪♪ ] When punk came and kind of intersected with heavy metal, it was like the political consciousness of the lyrics, and I could relate to that.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Ska being the original music of choice for skinhead kids that were actually not racist or were even anti-racist, that started to appeal to me as well.

For the first time in my life, I had the kind of friends that I felt like knew what I-- Maybe not what I'd been through before I met them, but they knew what I was going through.

We were all going through these things together.

And that group of people, a handful of us became anti-racist skinheads.

I think at first we decided to become skinheads as a way to do something edgy, something that appealed to us in an alternative sense, but it wasn't long before white-power neo-Nazi boneheads were being organized in our scene and in our city.

And that gave us a very clear enemy to identify.

We felt like we were fighting a war, and we were the only people who were going to do it because no one else was going to do it.

That really helped shape my identity in ways that I just wouldn't be the same person if that didn't happen.

Two of my teachers started to invest in my consciousness, in my political development, and they were like, "We see how driven you are, we see what you're doing on the streets, but you're going to be dead or in jail.

You're facing the symptoms.

What do you think about trying to learn about the root cause?"

Racism, white supremacy is a symptom, but the root causes of these things are deeper than that.

It was a morning, and I made this mistake that I'm still making sometimes.

I picked up my phone and started scrolling on social media, and then I saw-- Well, I saw this video of this Black man on the ground.

I didn't have to watch too much of the video before I thought, "Damn, that looks familiar."

The cruiser was familiar, the police uniform was familiar.

And then I realized I was watching Minneapolis.

I realized I was watching south Minneapolis, which is an area where I grew up.

Realizing I was watching another Black man being violently accosted by police, but I still didn't realize at the end of the, you know, eight, nine minutes he was going to be dead.

I had the day to process it, and I knew, I said, "People aren't going to stand for this.

A fight is coming."

CROWD [ chanting ]: Black lives matter!

Black lives matter!

Black lives matter!

♪ Despite the mental illness Quite resilient... ♪ OFFICER [ over speaker ]: --tear gas.

Leave the area now!

MIC: Historically, as an artist, I've always confronted these issues.

My primary creative choices have always been to tackle these issues head-on.

I've been in the streets using violence as a means of community defense and direct action.

I've seen what happens when cycles of violence become so engrained that there seems to be no end.

If there's any wisdom that I can draw from these experiences, the best way for me as a human being to try to impact things in a positive way is to be creative and to use art.

[ music playing over speaker ] The collaborative project that I've been part of with young people that is combining activism and education and my ability to produce music is an album called Rose City Rising.

And it's a collaboration on the production side between three different nonprofits: Outside the Frame, that teaches young people the arts of video production, Friends of Noise, that focuses on making sure that there are all-age venues and opportunities for young people to perform live music across the city, and then funding resources that are tied to Portland Public.

WOMAN: I picked this beat and I wrote a BLM song to it, and after I did that, Mic Crenshaw was also on the song.

He made the hook.

MAN: Mic Crenshaw's brought us all together on this compilation album to talk about all the events of last year and how it affected us, how it affected the world.

And to focus on our creativity on that.

MIC: So tonight, as part of the premiere of the films that Outside the Frame have been working on, Good Films About a Bad Year, these students that created these songs we got music videos produced for are going to premiere them on this big screen.

The youth took matters into their own hands.

I hadn't seen the music video before, so it was just nice to see how it turned out.

♪ I fight through All the hate ♪ ♪ I don't wanna be patient ♪ ♪ Don't say melanin Is the problem... ♪ It was amazing.

It was one of the best things I've ever done.

♪ Personal's political Political is personal ♪ ♪ Situation critical... ♪ [ crowd cheering ] Thank you so much for being part of the production!

Half my life at this point has been writing and performing, you know, touring, and being a hip-hop artist and a lyricist.

But now I'm venturing into literary forms of writing.

PM Press, the publishing company, heard my story as a Black skinhead, and they offered me a book deal.

And Black Skinhead, which is a memoir of my experience being a Black anti-racist skinhead, a founding member of a formation called the Minneapolis Baldies, which was an anti-racist skinhead crew.

I always want to be able to take what I'm witnessing and what I'm feeling and put it into language that is concise, but the intent is to transmute the pain and try to create something beautiful.

♪ America, can you feel me?

♪ ♪ To the people Where you at?

♪ ♪ Yo, holler if you hear me ♪ ♪ America, can you feel me?

♪ ♪ To the people Where you at?

♪ ♪ Yo, holler if you hear me ♪ ♪ America, can you feel me?

♪ One of the things I'm doing now is I'm trying to understand some of the deeper issues.

If we tend to want to put things in a binary, where there's the good guy and the bad guy, and there's good and evil and there's right and wrong, what are the things that we're hardwired to do as humans?

How much is conflict something that we actually just have to live with?

Is it a part of nature?

And where are we going?

Are we going to destroy our ability to survive on the planet?

And is there a way to turn it around?

So those are the questions I'm looking at.

And we'll see where it takes, you know, the art going forward.

♪ America, can you feel me?

♪ ♪ Freedom fighters Don't grow weary... ♪ Whee!

Get it, girl, get it!

All right, now let's kick forward.

ACOSIA: We are here on the Umatilla homelands.

All right, let's go.

The Umatilla, the Cayuse, and the Walla Walla people, we are the Plateau people of the Pacific Northwest.

Native people are doing everything today modern.

We're not just doing traditional things.

We are doctors and lawyers, we are artists.

Whoo!

I love to snowboard, I love to longboard, I love house music.

That was a fast ride.

[ sighs deeply ] We are living in all worlds, and we can show up in our indigenousness to anything as well.

My name is Acosia Red Elk.

I'm a jingle dancer and a yoga teacher.

[ rattling ] When I look back, I wanted to be a dancer so bad, but the reality that I was in, I never thought it would happen.

I went on to win a lot of competitions.

One year I won 42 powwows in a row.

That was interesting for me, because I had to learn how to start accepting myself, too.

Like, who am I to win this?

And that was something I learned along the way, to start loving myself and believing in myself, because I never did before.

This is "patishuay," it is white fir.

Before I like to really start handling my regalia, I always like to smudge.

I like to smudge my feet.

When I was young, we weren't really a powwow family.

My mom and dad owned an auto-body business, and they worked every day in the shop.

My mom is Scottish, Dutch, French, and Norwegian, with a little bit of Seneca and Mi'kmaq in her.

So she was this white woman that married this Native man.

When I was 6 years old, I caught on fire and burnt the backside of my body.

I spent three months in the Burn Concern Center in Portland, and that was really traumatic for my family.

My father started drinking again, and, um, he wasn't able to quit, and he died on my 9th birthday.

You know, it just sent me and my siblings into a downward spiral.

That just gives me a little more support.

And so when I'd go to the powwow, I would watch them dance, and I was so...

I was just in awe of how brave they were and how proud they were.

Fast-forward like two years, my sister got a dress made for me, and when I opened the Christmas present, I was super excited.

I was like, "Oh, my gosh!"

But then I realized that I was going to have to dance that night at the Christmas powwow, and I was so scared.

I just remember, like, stepping my first few steps out onto the dance floor, and I started crying.

I had been pitying my legs for the scars and what happened to me.

I was just pitying my life.

And then this was the body and the legs that were carrying me out onto the dance floor.

So it was just a really special moment, and it changed me.

I got the powwow fever, and we just hit the powwow trail.

My name's Paris Leighton.

This is my family.

This is my wife, Acosia.

Here's me putting on-- getting half dressed.

ACOSIA: And I learned a lot from my kids' dad.

He taught me how to make regalia, he taught me how to be a better dancer.

PARIS: Here's my lady.

She's completely dressed now.

Not all the way.

PARIS: Well, she's still got to put her feathers -and beadwork in her hair.

-My hair braids.

PARIS: We're ready to go into the powwow.

Granted, she starts at 1:00.

ACOSIA: Every dance has their origin story.

The men's traditional dance, you've got the feathers on their back, they're the warriors, they tell the story of their battle.

The women's jingle dress dance comes from a dream about 1915, 1920, during the Spanish flu pandemic, and a young girl was really ill and her father was a medicine man, so he went to seek vision.

And in that vision, he was brought into the sky by the Northern Lights people, and they sent him home with a gift that would heal the people and heal his daughter, and that gift was actually a sound.

And the people got well when they heard the sound.

And so they brought this dress to surrounding communities, and it grew and grew in numbers.

And then our dances were taken away from us, and it was outlawed to even practice your culture in that way, especially doing dances.

When we were allowed to be able to start practicing our culture again, they started having what they called a powwow.

People were coming from different tribes, and it was a celebration of song and dance.

And if you wanted to compete for prize money, you could.

And so it kind of became like a sport.

PARIS: It's pretty crowded in here, but as you can see, we make do.

This is the way we live every weekend.

ACOSIA: For a lot of people and for my husband and I for a long time, we didn't have work outside of powwow.

We just lived on the powwow trail and took part in our culture.

And there was years that we did 50 powwows in a year.

[ crowd cheering and drums beating ] But the Gathering of Nations in Albuquerque, New Mexico, it's the biggest powwow in the world, and basically if you win at that powwow, you're world champion for a year.

ANNOUNCER: Final two... [ crowd cheering ] ACOSIA: The first time I got first place at that one was like the biggest win I had ever had.

I was 24 years old, and I don't think anybody had won a contest there from my tribe.

It's interesting to think about growing up as a half-breed and sometimes feeling like, where do I belong?

ANNOUNCER: Your champion, right out here, spotlight time!

ACOSIA: You know, I had to learn how to start trusting my voice as a leader and gaining that confidence, knowing that I was carrying the name of my tribe with me and representing them, too.

Okay, so you guys are all just going to be looking up this way, and we're just going to start out with some basic steps, and we're going to find the beat.

And then we're just going to start moving through the different dance styles.

And with that came a lot of girls from our home wanting to become dancers.

So we're not just... loosely dancing, right?

That's how the guys dance.

They get really loose.

But the women dance like this.

They're proud-- look at my chin.

They keep their head up.

And if they look down, they look down and then look back up.

And they stay proud.

[ music plays on phone ] A little bit faster.

[ drum beating on phone ] Okay, ready?

Let's go, forward.

Try to be light as a feather.

This is where it starts.

They learn the steps, because those first steps are really hard to learn.

There's a lot of footwork and stuff involved, and all of that is good for the brain.

It's good for your joy, for your happiness, for your heart.

So crossing your feet.

And it ripples outward into the whole family.

You know, it's like that sound of the jingle dress.

It's the sound of the bells, the sound that the regalia makes.

It ripples outward and people feel it.

See how it has that sound?

Powwow dancing has just been a special gift for everybody.

[ exclaims ] Get it, girl!

Get it!

All right, now let's kick forward.

Now you guys, step backwards...

So we're just going to start out by just kind of arriving.

We already know where we are, and these are our homelands.

We're connected in every way to these lands.

And we've never got to practice in this park together like this, in this area.

This is part of the old July grounds, and our people used to camp here and have celebrations here in this area.

When I started yoga, my dancing became so much better.

I went to my first yoga class about eight years ago.

And then we're going to bring our hands to our heart.

Keep holding this.

In class, she said, "Take a deep breath... and let it go."

And I just started crying.

And I was like, "Oh, my gosh, I didn't realize that yoga..." I just didn't know.

Inhale, arms up...

In my mind, I was like, "Oh, my gosh, I have to get certified as soon as possible, because I want to travel around and share this practice with as many Native people as I can so that we can start healing faster."

Because we have a lot of trauma to heal from, and yoga can help us to do that.

Scoop up that earth energy and smudge yourself.

Let's just keep going, a couple more times.

This is the alarm-clock generation.

We've been hitting snooze for a long time, and people are starting to get up and wipe their eyes and look out of those foggy lenses.

People are using their voice and being brave.

[ Supaman's "Why" playing ] Everybody is looking to be a part of something special, something bigger.

And as indigenous people, art is a part of healing.

I got to do a collaboration with Supaman, he is a hip-hop influencer, and that was about six year ago, and that really opened the doors for a lot more modern collaborations, contemporary collaborations that I've been a part of.

♪ Who's gonna stop me ♪ ♪ When there's no one there To stop me... ♪ I got to do a really neat music video with Portugal the Man and "Weird Al" Yankovic.

Thank you so much for having us here.

We're so honored.

[ crowd cheering ] I am a part of Indigenous Enterprise, which is a Native American dance troupe.

We got to open a show in New York City for Indigenous People's Day.

They had built this circle in the middle, and nobody even knew we were coming out.

[ crowd cheering ] It was a lot of younger generation, and a lot of them had never seen that type of dancing before.

And so it was really neat to be able to know that they were exposed to modern-day Natives sharing the beauty of our pizzazz in today's world.

So we're coming back to ourselves, we're using our culture to be more strong today and sharing it with people so that we can build bridges.

[ Supaman's "Why" playing ] ♪ I wake up And I pray ♪ ♪ These are the words I say ♪ ♪ Visualize Your wildest dreams ♪ ♪ The time is now To put it down, it seems ♪ ♪ Actualize Your deepest thoughts... ♪ To see more stories about Oregon artists, visit our website... And for a look at what we're working on now, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

♪ Walls are distractions Pause and imagine ♪ ♪ Laws of attraction Positive action ♪ ♪ Bars and compassion Causin' reaction ♪ ♪ Walkin' my path And I'm confident, smashin' ♪ ♪ We come from everywhere ♪ ♪ We're something I don't care ♪ ♪ I see, I don't stare ♪ ♪ We've been right here For years ♪ Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S24 Ep2 | 11m 6s | Respected hip hop artist, Portland Poetry Slam champion and educator Mic Crenshaw. (11m 6s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB