OPB Science From the Northwest

Thomas Condon: Of Faith and Fossils

7/1/2022 | 30m 1sVideo has Closed Captions

Frontier preacher and pioneer geologist, Thomas Condon.

Frontier preacher and pioneer geologist, Thomas Condon was the first to recognize the scientific significance of The John Day Fossil Beds. He would devote his life to teaching and educating others about Oregon's ancient past.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

OPB Science From the Northwest is a local public television program presented by OPB

OPB Science From the Northwest

Thomas Condon: Of Faith and Fossils

7/1/2022 | 30m 1sVideo has Closed Captions

Frontier preacher and pioneer geologist, Thomas Condon was the first to recognize the scientific significance of The John Day Fossil Beds. He would devote his life to teaching and educating others about Oregon's ancient past.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch OPB Science From the Northwest

OPB Science From the Northwest is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

From historical biographies to issues and events that have shaped our state, Oregon Experience is an exciting television series co-produced by OPB and the Oregon Historical Society. The series explores Oregon's rich past and helps all of us - from natives to newcomers - gain a better understanding of the historical, social and political fabric of our state.

Video has Closed Captions

Before Apollo astronauts went to the moon, they trained in Central Oregon's Moon Country. (28m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the life of Linus Pauling, one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

In 1945 four young entrepreneurs decided to start an electronics company in Oregon. (29m 35s)

Video has Closed Captions

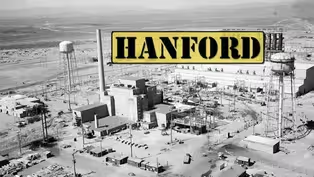

The Hanford project was a gamble in American history that changed the world forever. (59m 35s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[ ?

?? ]

MAN: "I once believed God created a small fact.

I now see he must have created a whole system of facts at once."

In 1853, a frontier preacher named Thomas Condon arrived in Oregon Territory.

He was always interested in the natural world, and especially in rocks and fossils and understanding how they got to be the way they were.

WOMAN: Condon was a storyteller, so he wanted to look at how does all this fit together?

What story does this tell about the Earth?

He would embrace Darwin's theory of evolution and challenge the church with the teachings of science.

MAN: The horses were really instrumental in helping people to see that Darwin's idea was correct, that you actually had evolution over time.

His contributions to understanding the ancient history of Oregon, that really is why he became the first state geologist of Oregon.

I think that he was not a man of his time.

I think he was way ahead of his time.

[ wind whistling ] [ ?

?? ]

Funding for Oregon Experience is provided by... [ ?

?? ]

MAN: "How strangely out of place a score of palm trees, a hundred yew trees, or even a bank of ferns would seem here now.

And yet here these once lived and died and were buried."

-- Thomas Condon John Day Fossil Beds is really the only place in the world where for the last 65 million years -- the age of mammals and flowering plants -- we have a very long record of time all in one place, nearly 50 million years of time, all preserved here in Eastern Oregon.

Every year, thousands of people visit the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument and this place, named for the man who first revealed its secrets.

When Thomas Condon came here to Oregon, he was excited by the fossils he found and that other people brought to him, and he wanted to learn everything he could about them.

Thomas Condon's journey through time begins far from Oregon, where he was born in Ireland in 1822.

His father was a stone cutter.

WOMAN: "There was a limestone quarry near the home of Mr. Condon's childhood that must have made a deep impression upon his thoughtful mind, for his interest in geology began with his childhood."

-- Ellen Condon McCornack When young Thomas was 11, the family immigrated to New York.

There, Thomas excelled in his studies, and by the time he was 19, he was teaching school and gathering fossils in Upstate New York.

A devout Christian, he would choose the ministry as a career and enter a Congregationalist seminary.

MAN: Well, when he was in seminary, he didn't just study scriptures and learn about the theology of his group, but he also did a lot of reading of current scientific thought.

And he was learning about the geological processes that scientists were beginning to invoke for how rocks and fossils had gotten to be where they were on the planet.

And he spent a lot of his time teaching people, and a lot of his decision-making in his life was motivated primarily by finding ways that he could educate more people.

In 1852, at 30 years of age, Condon would find his calling as a home missionary.

He married a 20-year-old teacher, Cornelia Holt, and together they embarked on a four-month voyage around the horn of South America.

[ ?

?? ]

Their first assignment: untamed Oregon Territory.

Condon's fossil collection came along.

Part of his reason for being out here was to bring civilization, to bring learning, challenge people to think.

This to him was a mark of civilization, and that was just as important as bringing -- bringing the gospel to the people was to bring civilization.

MAN: "Cornelia and I have arrived in good health and good spirits.

I trust we shall soon go to work with a cheerful courage."

-- Thomas Condon, 1853 The Condons went to work in the remote town of St. Helens on the Columbia River.

But the next 10 years would be rough going from the start.

St. Helens didn't work very well for Condon.

Condon was teaching school in order to make ends meet, never gathered much of a congregation.

Condon would move to Forest Grove, then further south to preach in the area around Albany.

But he would struggle always with meager pay and competition from other churches.

Three strikes and you might think "out," but then he was sent to The Dalles.

[ ?

?? ]

The year was 1862, and gold was king.

Strikes across the Northwest, including Eastern Oregon and Idaho, had turned The Dalles into a boomtown and major supply hub for miners.

WOMAN: Thomas Condon's predecessor here, William Tenney, made the comment that The Dalles was the hardest place he had ever been and that it was all drinking and carousing and fighting, and it was just a very wild place.

Now, the church was not thriving.

There were only five members, and two of them lived 20 miles downriver.

They met here in the old courthouse, and the accommodations were not very promising.

BISSET: When the floorboards were laid, they were green, and they shrunk.

And so it was a handy route for smoke and vermin to come up through the floors.

VERCOUTEREN: The drunks and the people who were locked up on a Saturday night downstairs in the jail cells, they would sing along with the hymns, often with bawdy lyrics.

BISSET: I imagine it was a real challenge to come to church on Sunday morning.

But the small congregation began to grow.

WOMAN: "Mr. and Mrs. Condon were people of fine personality and made many friends."

-- Lulu Crandall VERCOUTEREN: He was a learned parson, and so he was the person that you went to when you had questions about almost any subject.

BISSET: He could talk to anybody, really loved geology, and just had this penchant for wanting to share.

Within six months, Thomas Condon had raised enough money in the community to build what he called "the prettiest church in Oregon."

And it wasn't long before he was being described as carrying a Bible in one hand and a geologist pick in the other.

BISSET: He hiked a lot.

There was a rock quarry up on the hill, and he would wander around up on the bluffs, maybe sit in the rock quarry, and gather his thoughts and write his sermons.

While hiking the hills, Condon would often visit Fort Dalles, home to a division of Oregon's volunteer cavalry.

DAVIS: At the time, the federal government viewed the tribes in the area as dangerous, and so they were trying to protect the pioneers, the settlers, from the tribes.

And so they had a large number of soldiers who were out patrolling and trying to make sure that there wasn't any hostile activity.

Commander John Drake and many of his men had become friends with Condon and fascinated with fossils along the way.

While camping on a long reconnaissance mission up the John Day Valley, his men pursued a new pastime.

MAN: "I found our camp converted into a vast geological cabinet.

Everybody had been gathering rocks."

-- Captain John Drake, 1864 Soldiers are bringing him things.

He's really curious.

He knows from reading some of the most recent reports from geological surveys in the Midwest that the things that they're finding are really important.

In 1865, Thomas Condon decided to explore Oregon's interior for himself.

DAVIS: So essentially he goes out in a military party, the lone scientist with a whole horde of soldiers around him to keep him safe, and then they all end up collecting fossils together.

[ ?

?? ]

The area would soon draw Condon back.

MAN: "Of this new region, I can say without hesitancy it is the wildest, strangest, most wonderful place in all this most wondrous country.

The fossiliferous rocks were arranged into galleries, each painted in the brightest hues of red, green, white, and endlessly mixed into neutral shades between.

The first important fossil we found suggested a name for this cove-like depression among mountains.

It was a fossil turtle, and we named the place Turtle Cove."

Today, the area is known as Blue Basin, part of the Sheep Rock Unit in the John Day Fossil Beds.

The rocks behind me are between about 31 and 28 million years old.

The stripes you see, those bands of color, those are individual soil layers that were laid down over thousands of years and just stacked on one another with volcanic ashes intervening.

The volcanic ash, the lava flows, those all produce the material that help the rock layers build up and bury fossils and preserve them.

And the fossil record here really is largely attributable to the fact that we have this long volcanic history.

We know today from looking at the exquisite collection of fossils from the Clarno Nut Beds this was a very lush sort of subtropical volcanic area that might have looked a lot like Costa Rica does today, with tall volcanoes peeking out of a jungle-y, vine-covered vegetation that would have included early citrus trees, early versions of coffee trees.

The time period that's preserved here is actually a time period of change.

It's when the forests first started to open up and when we first started to get open habitats, and so there's lots of new experiments of animals trying to take advantage of those new open spaces.

DAVIS: This is one of the three tortoise shells that Thomas Condon brought back from his first trip to Turtle Cove.

So this yellow number right here is Thomas Condon's number, and then this number is one that we added separately later to put it into the museum's main cataloging system.

This is a rhino skull that Thomas Condon collected.

It was an animal that was probably a little bit bigger than a really big modern horse, like a Clydesdale, but not as big as a modern rhinoceros.

This is a lower jaw of a rhino that's the same size, so this may actually be the jaw that goes with that skull.

SAMUELS: A lot of what Condon was finding were mammal fossils, and, in particular, things like oreodonts.

They're actually most closely related to camels.

They've got kind of a squat, pig-like body and big pig-like tusks, but the teeth and their jaws actually look a lot more like something like a camel.

There were saber-toothed nimravids, huge skulls of entelodonts.

And in the case of Blue Basin, we have almost a hundred species of mammals that are known from here.

Really, you can't go anywhere in North America today and find that great of diversity.

Back in the mid-1800s, paleontology was an exciting new field of discovery.

Darwin's The Origin of Species had been published in 1859 and first popularized the idea of natural selection.

All of a sudden, fossils become much more important to help us understand that process, to help people who are incredulous see whether or not they could believe that that was what was going on.

At that time, and really in some circles still today, the idea of evolution and change through time was a contentious one.

It was something there was a lot of debate about.

And what Condon can see here, he could see change.

MAN: "Evolution was simply God's method of working, and therefore not atheistic or infidel.

The Church has nothing to fear from the uncovering of the truth."

-- Thomas Condon It would be Thomas Condon on the one side against, you know, the philosophy professor on the other side, who would be arguing for a strictly biblical, literalist view of the origin of the Earth.

Well, he believed that, you know, six days was a poetic way of stating large gigantic epochs of prehistory, and he could see the evidence in the rocks.

Thomas Condon would play a critical role in uncovering evidence millions of years old.

Early in his explorations, he began discovering fossilized jaws, teeth, and partial leg bones from small, three-toed ancestors of the modern horse.

MAN: "Many of these fossils indicate a really beautiful little animal of graceful outline, bringing to that early period a truthful prophecy of our modern horse."

DAVIS: Oh, it would have been the size of like a medium-sized dog.

The shape of the way the teeth grow is the same for this little guy as for a modern horse.

So somebody who did their anatomy studying in the 19th century would have done a whole lot of horse anatomy, because horses were really important.

And when they saw this, they would be struck by the semblance.

By now, Condon had been corresponding with prominent East Coast paleontologists, including Dr. Joseph Leidy, Edward Drinker Cope, and Yale University professor Othniel C. Marsh, all in fierce competition to identify new specimens that would support Darwin's theory.

Condon sent them fossils from the John Day Valley to examine and return.

Here are some of the specimens that Thomas Condon sent on the Transcontinental Railroad to Leidy to publish.

And so this one we can actually tell when Thomas Condon prepared the specimen to send off, because the date is captured in the newsprint that he used as he was prepping the specimen, so April 14, 1870, or thereabouts.

And so even though he could tell it was something new and he would have been able to do the work of actually identifying it and writing up the paper, he sent it to an established scientist so that that person could do the work and get it into the literature.

SAMUELS: The first thing that was sent to Leidy, that was actually a horse specimen, by Condon.

And Leidy described that in his 1870 paper, and he called it Anchitherium condoni.

Later on, the naming of these things changes.

Today we call that horse Miohippus.

Marsh was most intrigued by the horses that Condon was finding, because the horses Condon found fit into the story of horse evolution that Marsh was beginning to build.

And then he could see that he'd found these little, multi-toed, three- and four-toed horses from the Great Plains.

And Thomas Condon was finding horses that were just a little bit bigger, had a little bit smaller toes, side toes, than those horses.

In 1871, Condon would lead O.C.

Marsh on the first university expedition into the upper John Day Valley.

Marsh would go on to write one of the most significant papers on the evolution of the horse at the time, but failed to credit Condon for his discoveries.

SAMUELS: In the case of the horse that Condon found, Miohippus, when that was described by Marsh, he really called it the missing link in horse evolution, because it pointed to a progression in his mind from the earlier, more primitive horses more towards the horses we have today.

Thomas Condon loaned him specimens.

He expected Marsh to work on them and then to send them back to Condon so that he could keep them for the people of Oregon, but that wasn't Marsh's intention.

Marsh never returned those specimens.

In the meantime, Condon continued to share his discoveries and knowledge.

Soon after arriving in The Dalles, he'd begun giving public lectures on the state's natural history, using his fossils as illustrations.

MAN: "Mute historians are they of a far distant past, uniting with hundreds of others to tell strange stories of the wonderful wealth of forest, field, and lakeshore of that period."

BISHOP: There would have been early versions of rhinos here called brontotheres.

I think he made the landscape come alive to people, and that's -- it's a rare quality.

And by the late 1860s, he'd begun writing his own articles about Oregon's ancient past, not for scientists, but for a general audience.

Oh, he was very much interested in popularizing scientific knowledge.

The people of the town, I think, took great pride in that, and they were learning things.

And the combination of his lectures and that collection was very important to people here in The Dalles.

Their home was turning into a mini-museum.

Sometimes people would come from far and wide to see those fossils.

[ ?

?? ]

BISSET: There was a fire.

All the houses around his burned down.

And not only was his house saved, but the neighbors came in and took all the fossils and furniture and got them out of the house.

And after the fire was over with, one by one, the neighbors and the neighbor kids brought the fossils back.

His collection was, I think, an essential part of himself.

I think that he -- you know, he wasn't -- he wasn't the kind of man driven by avarice and a desire to own beautiful things.

But those fossils were not just beautiful things to him.

They were important pieces of God's work.

And he really needed to have them there not for himself, but for everyone else.

The early 1870s would be a time of change for the Condon family.

Their eldest son, Eddie, died of pneumonia at 18.

MAN: "You can imagine the deep shadow it cast over life for me and my family.

What I have lost, no one but myself can measure."

-- Thomas Condon Eddie was kind of a protégé of Thomas.

And he was very much interested in the fossil collecting and the rocks and accompanied Thomas on trips down into the John Day country.

With the death of Eddie, Condon now focused on providing an education for his older children, and he wanted his family near a university.

About the same time, state legislators decided to appoint Condon Oregon's first state geologist.

DAVIS: It was a proper recognition of his stature in the state.

I think for the longest time, Thomas Condon was the best-educated man in Oregon, and he was serving in this role, essentially, as state geologist well before they named him and started paying him for the duties.

But they also thought that if they hired him that he would keep preaching, and all the pieces didn't fit together.

At a turning point in his career, Condon resigned his missionary post in The Dalles.

In addition to becoming state geologist, he accepted a position teaching geology at Pacific University in Forest Grove, where Eddie had attended school and where his older children would receive free tuition.

Then, three years later, a brand-new state university opened its doors in Eugene.

Thomas Condon arrived at the University of Oregon; he was the department of geology and he was the department of chemistry and the department of physics and the department of geography and the department, you know, of any of the sciences, because that was his role, was actually to teach all science at the University of Oregon.

He was extremely popular as a teacher.

Most of the learning in college at that time was rote memorization.

He wanted people to actually understand.

The university administration required him to name a textbook, and he did, but he didn't use it.

Every table in the room was actually a glass-top cabinet full of fossils, and then he'd use the fossils for the lessons to teach the students about biology, to teach them about geology.

He was also a field-based teacher.

You can wander through Oregon caves on a tour, and lo and behold, there's Thomas Condon's signature and the names of the students who were with him.

To encourage women to go into science was almost unheard of in the early 1900s.

Women were lucky to be a lab technician.

And he actively encouraged women to come into his lab to work with him, to go with him in the field, and that was an astounding thing.

It's part of his courageous nature.

DAVIS: The first valedictorian of the University of Oregon was Thomas Condon's daughter, Nellie.

So she was part of the graduating class of 1878.

Over the years, Thomas Condon would become one of the most beloved personalities in Oregon, his nature walks greatly anticipated.

MAN: "At an early hour last Saturday, Professor Condon, accompanied by his university class, started for the top of Spencer's Butte, quite a large number of our citizens following in procession."

-- The Eugene City Guard As the Condons grew older, they often spent summers at their Nye Beach cottage, where visitors were always welcome.

And when Thomas lectured on the beach, young and old gathered intently around.

WOMAN: "And when the talk was over, the motley gathering strolled leisurely away, but the rolling breakers at their feet, the hurrying scud, and blue summer sky all had a new significance as they pondered on the mystery of creation."

-- Ellen Condon McCornack In 1902, at 80 years of age, Thomas Condon published a geological history of Oregon.

The title referred to Oregon's most ancient lands, the Blue and Klamath Mountains that once rose from the sea.

DAVIS: What he saw were two areas of Oregon with really, really ancient fossils that must have been from when this area was all in the ocean, deep in the depths of time.

And because he didn't know about plate tectonics, he viewed the history of Oregon as a history of two ancient islands, and that over time, the space between them got filled up with younger and younger sediment.

SAMUELS: But Condon really recognized very early on that those rocks in the Klamath Mountains and the Blue Mountains were very old and that they were representing marine rocks.

And that is kind of a foundation that our understanding today is built upon.

By the late 1800s, a new generation of paleontologists, inspired by Condon's work, was now exploring the fossil beds of the John Day Valley.

Their focus on the area would further promote its preservation as a world-class scientific treasure.

Also at that time, people were trading fossils between museums.

And so really, most major museums in the world have fossils from John Day Fossil Beds as a result of these early efforts.

Always learning and always exploring, Professor Condon would teach at the university for nearly 30 years.

The student body, I believe, said they wanted to name a building after him.

And he was too humble a man to let them do that, so he said, "Name these trees after me.

They can be dedicated, because they're important, growing, living parts of the Earth."

Those were the only two trees that were growing on what's now campus when the university was founded.

In 1907, Thomas Condon died.

He's buried in Eugene, alongside Cornelia, his wife of nearly 50 years.

His original collection of fossils continues to grow at the University of Oregon.

DAVIS: He wanted the collection to stay intact as a single record of Oregon's geology.

And not just that, he had fossils he had traded to get so that he'd have important specimens from other areas to teach with, and so those were all really essential things in his view for preserving Oregon's heritage.

The Condon Collection is a living collection, because we're still collecting and adding to it today.

SAMUELS: And so we've got here visible is part of an oreodont skull.

Things like this are constantly eroding out of these hillsides, and this is how we hope to find it, with just part of it exposed.

There's a lot of responsibility in protecting this place, because it's really important for the American public, and setting this aside and preserving it and helping people understand it, that's a very important mission.

Condon very much has inspired me.

He's inspired me to try to help people understand the ground that they walk on and the history of Oregon and the history of the Northwest.

I think he should be an inspiration for all of us.

This man was able to see the big picture and how everything all fit together, religion and science.

He helped a great many people see that point of view.

MAN: "Here in what is now Oregon, a broad and deep chasm in the history of life was brought upon the lands and upon the waters.

Our inquiries have only reached the threshold."

There's more about "Thomas Condon: Of Faith and Fossils" on Oregon Experience online.

To learn more or to order a DVD of the show, visit opb.org.

[ ?

?? ]

Captions by LNS Captioning Portland, Oregon www.LNScaptioning.com Funding for Oregon Experience is provided by...

Recent Discoveries at the John Day Fossil Beds

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 7/1/2022 | 2m 33s | Recent Discoveries at the John Day Fossil Beds (2m 33s)

The Scientific Significance of The John Day Fossil Beds

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 7/1/2022 | 2m 6s | The Scientific Significance of The John Day Fossil Beds (2m 6s)

The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 7/1/2022 | 1m 59s | The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center (1m 59s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

OPB Science From the Northwest is a local public television program presented by OPB